Appleby History > Alan Roberts > Early Modern Villagers > Labourers

Appleby Families: Villagers in Early Modern Times

Part 6: The Labouring Population

'A poor, beggarly sort of people'

by Alan Roberts

Agricultural day-labourers shared the bottom rungs of the status ladder with the itinerant poor. By 1700 they comprised about a quarter of the Appleby householders in the register. The actual proportion of labourers in each parish was seasonally increased by casual labourers, pieceworkers and servants in husbandry. Professor Everitt has suggested that at least a third of the inhabitants of midland parishes worked as agricultural labourers at one time or another. Economically there was little to distinguish between poor husbandmen, cottage craftsmen and day-labourers. Under the Statute of Artificers of 1563 all males between the ages of twelve and sixty who did not belong to one of a number of specifically defined occupational categories were regarded as wage labourers. This occupational title therefore functioned as a convenient tag for all those who had no other livelihood to fall back on. Labouring was an age-specific occupation. Smallholder's sons hired themselves out as labourers while waiting to inherit the family holding, or to acquire sufficient capital to set themselves up as husbandmen. As we have seen some retired farmers became 'labourers' when they disposed of their lands.

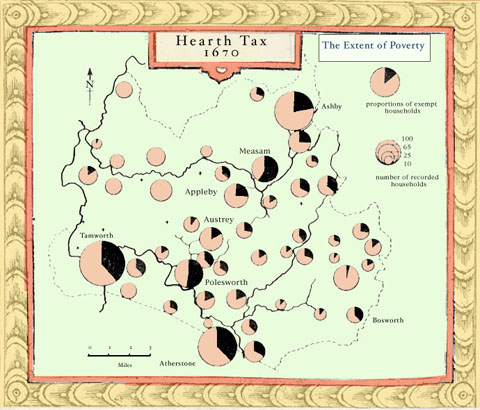

Hearth Tax Exemption

Click for larger view

Hearth tax exemption certificates confirm a later impression of labourers in the midlands as 'a poor, beggarly sort of people apt to run in Arrears'. In 1670 at least 4 of 17 exempt householders in Appleby were labourers. Few labourers had the requisite £5 worth of goods and chattels to warrant drawing up an inventory when they died. Those few labourers' inventories that have found their way into the archdeaconry court files testify, almost invariably, to a frugal existence. Henry Durden and Thomas Mosely of Appleby, whose goods were appraised at £5.19.0 and £4.0.6 respectively, are probably typical. Both escaped the hearth tax on the grounds of poverty and both had outgrown family responsibilities. Henry's will and inventory (1658) shows that he dwelt in a two-roomed cottage which he recently erected himself on land purchased from one of his neighbours. Thomas had even less, for there is no mention of land or farming gear among his goods, merely some bedding and a few sticks of furniture.

The relegation of labourers to the bottom rungs of the status hierarchy is suggested by their growing physical isolation from the landholders. Constables' accounts and quarter sessions orders reveal that poor, itinerant labourers commonly found refuge on the waste ground on the outskirts of open-field villages. A colony of landless labourers and poor widows was established on No man's Heath by 1660. Some at least of the 17 Appleby householders granted exemption from the 1670 hearth tax, and all 9 of the Austrey householders 'that receive weekly collection and live upon the common' in 1671, were encamped upon the heath. Apart from servants and apprentices, who moved where they could find work, labourers were the most geographically mobile group in the parish. A precarious living encouraged frequent short-term migration between parishes in search of work or charitable support.

Thirteen new labouring family surnames were introduced into Appleby between 1640 and the turn of the century, an approximate doubling of the number of labouring families presenting children for baptism. We don’t know whether the householders bearing these surnames had always been labourers, or how many labouring families died out or left the parish before 1700 as the Appleby register only begins to record occupations from 1698.

Sources and Notes

Everitt cites Coleman's estimate that 47% of the population of England in 1700 were either labourers, cottagers or paupers: AHEW IV, 399; Cf. 17 of the 41 Austrey householders recording baptisms between 1561-80 (41.4%) were labourers.

William Cater, 1632, The ambiguity of the term 'labourer' is exemplified in the progress of Richard Mosely of Appleby through an occupational life cycle. He is described as a labourer in the Appleby register in 1665 but identified in 1675 as a 'husbandman' in a deed attached to a marriage settlement (L.R.O. DE 797). In 1682 and 1686 he is again referred to as a 'labourer' (Appleby PR 1682; wills, 1686/45; inventory, PR I/88/61). Richard was worth £40.6.8 at death which shows he was far from impoverished. His change in status may indicate that he ceased farming between 1675-82 to work for wages, thereby reverting to a 'labourer'.

A midland surveyor (c. 1700) cited in B.K. Roberts, Rural Settlement in Britain (London, 1977), 194.

See, for example, probate administration of Samuel Heywood of Appleby (L.R.O. wills, 1737) which advises that deceased goods not worth £5.

L.R.O. PR I/64126; PR 1/23/117.

L.R.O. wills, Henry Durden, 1665/19; His son Thomas Moseley was exempt from hearth tax in 1670 (P.R.O. E 179/332).

L.R.O. wills, Thomas Moseley, 1672/91; Hearth tax exemptions: 1670-3.

'Squatter settlements' provided fertile recruitment for radical religious sects before 1660: See A. Everitt in Thirsk, AHEW IV, 411; cf. further references to squatters in C. Hill, The World Turned Upside Down (Oxford, 1975), 282, 290.

Cf. WCR Hearth Tax Returns, 10; P.R.O. E 179/332, E 1791347; One example is probably Thomas Robinson sen. a quaker descended from a family of Austrey smallholders. He was called pauper and exempted from paying hearth tax in 1670, and later described at his death as a labourer. Between 1679-85 he and his wife were repeatedly brought before the Quarter Sessions bench for non-attendance at church. In 1694 his widow was forced to 'renounce the burden' of his estate to the principal creditor. WCR Quarter Sessions Indictments VII, 141, 148, 180-1.

©Alan Roberts

Next Section: Servants