Appleby History > Alan Roberts > An Appleby Penitent

An Appleby Penitent

"Clothed in White Sheets" in 1741

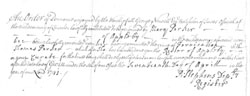

Today, despite public concern about teenage pregnancies and unmarried mothers, most would be shocked by the sight of a seventeen-year old girl standing in church on Sunday morning draped in white robes and carrying a white wand, “openly and publicly” confessing to the “grievous crime” of fornication. This was the sight that greeted the parishioners after morning prayers in Appleby parish church on Sunday 19th April, 1741. The ghostly figure draped in a white sheet was one of the local girls. The villagers were witnessing a comparatively rare event even for those times, an ancient ritual act of penitence legally set out and sanctioned by the Established Church in atonement for sexual impropriety. In a sworn statement read aloud to the congregation the penitent Mary confessed to an illicit sexual liaison with Thomas Parker, describing her actions as a breach of God’s “sacred laws”, an “evil example” to others that threatened her immortal soul. Mary humbly acknowledged her scandalous behaviour, begging her neighbours to forgive her and asking for Christ's grace “to avoid all such sinful wickedness”, so that she might live a sober and righteous life in the years to come. She ended her confession by asking the congregation to join her in reciting the Lord's Prayer.

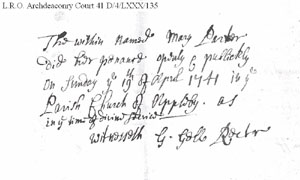

The discovery of the official certificate confirming Mary's open confession in the archives of the Leicester archdeaconry court, invites us to investigate the circumstances, the personalities and the events leading up to this public show of remorse. The actual transcripts of the court proceeding that might be expected to throw light on the circumstances of the case have not survived, but similar cases from other parishes suggest that there would have been a fairly lengthy and thorough investigation by the archdeaconry court officials. The archdeaconry courts dealt with moral offenses and sexual transgressions, hence their popular reputation as “Bawdy courts”. Cases of this sort were generally brought to the attention of the archdeacon's office by the churchwardens at the behest of the parson. If the ruling involved a penance it would be drawn up in the archdeacon’s office by the notary or archdeacon’s official, here identified as a Mr George Newell, Bachelor of Laws. The prosecution witnesses were examined privately and asked to answer a list of questions or “interrogatories”, drawn up by the defendant's proctor, or legal representative, to ascertain whether the witnesses were reliable and neither prejudiced nor bribed, as indeed occasionally happened, as in the case brought by John Winter against Thomas Petcher of Appleby relating to an incident at Atherstone Fair in 1598. Attempts to discredit witnesses as biased or bribed were by no means unusual. In this instance however, there is no dispute about the actual events and the facts are clearly admitted without equivocation, with Mary's open confession that she was “led by instigations of the devil and mine own carnal concupissence” - the standard formula used by the archdeaconry court officials for cases of this sort.

The part played by the Appleby rector is of particular interest. The Reverend George Gell had been instructed by an order from the church office two days previously. He probably played some part in drafting the words of Mary's confession, and he almost certainly organised and personally supervised the occasion. Richard Dunmore has pointed out that the plan of the pews from 1832, prior to the 19th century restorations, shows the interior of the church as a “Protestant preaching box” with the minister's pulpit and desk occupying a central position (In Focus 26). At the foot of the pulpit and desk, a bottom step or platform projected into the central space between the pews. Perhaps this was where Mary was made to stand to say her penance in full view of the congregation. Considering the events and the religious climate around 1741, midway through the reign of George II, Gell’s apparent enthusiasm to reform the morals of his parishioners seems to hark back to an earlier age. Was he a “Godly puritan” determined to stamp out immorality in the parish, or was he merely conscientiously, perhaps even reluctantly, carrying out his religious duties after an offence had been brought to his attention?

The comparatively late date of the penance invites further speculation. This ancient church ritual must have seemed anachronistic in the more tolerant and relaxed religious climate of George II’s reign. In this “negligent” age (as one writer describes it) the church’s influence was waning under an onslaught of radical and secular new ideas challenging the established order. By the mid eighteenth-century, with the growth of dissent and widespread non-attendance at church, the operations of the church courts with its ritual penances and threats of excommunication were already regarded in some quarters as archaic relics of a bygone “medieval” age. Despite this, Mary’s penance is clear evidence that the church authorities in Appleby were determined to discourage licentious and wanton behaviour threatening the parish community. It may well be that the rector selected Mary Parker to be charged as a warning to other offenders in the village.

Morals offences, cases of illegitimacy, defamation or fornication, were customarily dealt with by the ecclesiastical courts. Before the ecclesiastical visitations a list of questions or “visitation articles” would be sent to the churchwardens, asking them to report on a wide range of matters to do with the upkeep of the church, the conduct of the clergy and as in this case, the moral behaviour of the laity. The Thirty third Article of Religion clearly states that those who commit moral offences “ought to be taken of the whole multiple of the faithful, as a heathen and a publican, until he be openly reconciled by penance and received into the church”. The normal punishment for fornication was the performance of a penance with the citation delivered personally by the apparitor, or court messenger. The birth of an illegitimate or “base” child was usually regarded as sufficient evidence that the offence had taken place. Those accused of morals offences were usually cited to appear before the archdeaconry court under threat of excommunication (or “lesser excommunication” in less serious cases of this sort). A certificate would usually be issued after the penance was performed and a notice of absolution would be read out, the necessary fees were disbursed and there the matter rested. Although these practices were beginning to die out by the middle of the eighteenth century, the clergy reluctant to make presentments for “matrimonial” offences in these more relaxed and tolerant times, much still depended on the determination of the local parson to pursue offenders (Warne, pp 20-21).

The stern and unequivocal tone of this document from 1741, prompts us to examine the background and character of its instigator, the Reverend George Gell, by then a sprightly 67-year old. Gell’s appointment as Appleby rector from 1717 until his death in 1743, followed a long clerical succession of Moulds who held the advowson, and who passed on the incumbency from father to son for several generations. Both he and the Appleby churchwardens obviously took their pastoral responsibilities very seriously. In a comparatively “closed” village like Appleby, the rector would have naturally aligned himself with the parish elite. Born in 1674 the son of Thomas Gell and Mary Spencer of Wirksworth, he could claim family connections to the Gells of Hopton Hall, a prominent Derbyshire landed family active in the church, the Army and the Navy. Before securing his appointment as rector of Appleby, Gell was vicar of Thurning in Huntingtonshire where, in 1715, he married Catherine Swetnam who subsequently bore him three children. In 1740 the marriage of his youngest daughter Catherine to George Moore, lord of the manor of Appleby Parva, would have further consolidated his position in Appleby. As the Gells were staunch Presbyterians we might be tempted to see George as one of that “black-coasted army of clerical intelligencia” described by Jonathan Clark, imbued with a mission to stem the tide of immorality and to re-assert ecclesiastical discipline under the influence of movements like The Society for the Reformation of Manners (1691) and The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (1698). Clark sees this renewed evangelical zeal as the clergy’s reaction to a marked decline in morals following the Toleration Act of 1689 which had “shattered the coercive machinery” of the church (p. 277). The church’s newfound mission to enforce moral discipline is in marked contrast to the situation a few decades earlier when the local clergy had other things to think about. In 1715 at the time of bishop Wake’s visitation, the deplorable condition of the church fabric appears to have been their major concern. The parson of Appleby, Gell’s predecessor, was complaining about the church being badly in need of repairs, with poor attendances, rowdy children and swine breaking through the fence into the churchyard (Visitation cited in Pruett, p.119).

The penitent Mary Parker was probably from a farming family well established in the parish. There were Parkers living in Appleby as far back as Tudor times, and even earlier. They mostly appear in the parish register and probate documents as farmers, freeholders, smallholders or traditional craftsmen. In 1642 a Francis Parker signed the Protestation Oath. One of the Parkers who left an inventory was described in 1684 as a carpenter. In 1724 a yeoman called Thomas Parker left an inventory worth a modest £20.10., suggesting that he had retired and disposed of his estate. Another Thomas Parker, also described as a yeoman and probably his eldest son and heir, a fairly prosperous dairy farmer, left an inventory assessed at £226.5.6 in 1735. The younger Thomas Parker’s inventory is unique in that it names every one of his beasts individually, including a red cow called “Parson” and another called “young Jerimmy” (18th Century Inventories) Thomas Parker and his son both appear to have occupied a tenement called “Ducklake”, near the Town Meadow which is several times mentioned in the wills and conveyances. These same Parker lands may passed down to Mr. James Parker, who is listed among the Appleby freeholders in an early election roll. The Parker lands at the northern end of the parish, adjoining the Town Meadows and abutting onto Over Street, may well be the 47 acre and 157 acre farms belonging to two Parker families recorded in the 1881 census, and clearly shown on the 1883 map of the Appleby Hall Estate. Mr Dunmore has pointed out that one of the Parker farmhouses and outbuildings was still standing alongside the brook on Ducklake Lane until as recently as 1969 when the last surviving Parker sold up and the land was redeveloped for housing.

The Mary Parker who registered her bastard daughter, Sarah, in Appleby church on 3rd December 1740 is almost certainly the same Mary Parker ordered to perform a public penance in the church four and a half months later. Although we cannot be absolutely certain of her exact identity, all of the available evidence suggests that she was the daughter of John and Anne Parker, baptised in Appleby on 19th April, 1724, exactly seventeen years to the day before the penance. The “William & Dorothy” named alongside Mary Parker on the cause list are most unlikely to be Mary’s parents, as there is no further mention of these individuals nor any written record linking them to the parish. John and Anne Parker on the other hand were well established in the parish and had already registered the baptism of their son, Thomas, (presumably Mary’s eldest brother), on 4th February, 1719. Another Thomas Parker, who was probably related to the Appleby family, the son of John and Jane Parker, was baptised in Norton-juxta-Twycross on 3rd August, 1718. There are therefore two likely possibilities for the identity of Mary’s co-accused “Thomas Parker, the son of John Parker” – her brother born in Appleby or the Thomas Parker whose baptism was registered in Norton. Both would have been in their early 20s in 1740, the time of the alleged offence. Of these two “likely suspects”, Thomas Parker from Norton seems the most obvious candidate as Mary’s lover and presumably the father of her child. While they may have been related in some way, we have no reason to think that they were siblings, as incest was a serious matter and one would expect some specific reference to it in Mary’s confession. Although we can never be absolutely certain, the very absence of any mention of incest, or any evidence to suggest that the accused Thomas Parker was charged by the court, or required to perform a penance, tends to discourage such speculation.

We are led to assume that Mary was singled out by the rector as an example to discourage immoral behaviour in the parish, an attempt in particular to express the church’s disapproval of unmarried women having illegitimate children. The Appleby register reveals some further curious aspects of this case. It may perhaps be significant that Mary’s parents had already baptised a child called Sarah on 9th February, 1735, six years earlier. Strangely, on 15th April, 1741 – just four days before Mary’s penance - James and Sarah Parker brought their infant daughter, Elizabeth, to be christened in the same church. The court indexes reveal that between 1740 and 1744, sixty-two of the 136 cases heard by the archdeaconry court in its monthly sessions were for fornication, with most of the others for defamation or rowdy behaviour. Why was Mary the only offender required to undergo a public penance? While the Act Books for 1731-1743 have been lost the number of matrimonial cases was much reduced compared to earlier decades. This document is therefore a rare find, the only known eighteenth-century penance certificate that exists for this part of Leicestershire. Even in the 1740s, this humiliating ritual must have been seen by most of the villagers as an amusing anachronism harking back to the olden days, a throwback to the immediate post-Reformation period. In finding explanations as to why the case was initiated in the first place, the rector’s social background, his position and the forty-year generational gap between he and the penitent Mary Parker is probably sufficient. After the matter had been resolved there is no evidence of any further cases being brought forward, and no further mention of Mary or Sarah, in the Appleby records. We do not even know whether or not Mary stayed in the parish. By December 1743 the rector himself was dead and the incident probably soon forgotten.

References

A.Warne, Church and Society in Eighteenth Century Devon (New York, 1969) pp. 20-21, 76 .

J.C.D.Clark, English Society, 1688-1832 (Cambridge 1985, 1991), The Church in an Age of Negligence, 1700-1840 (1988)

J.H. Pruett, The Parish Clergy under the Later Stuarts: the Leicestershire Experiment (University of Illinois, 1978).

Handbook of Records of Leicester Archdeaconry Court (Leicester Museum, 1954)

International Genealogical Index (IGI)

The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester & Rutland (L.R.O.)

Act Books Correction Courts 1D41/13, Appleby Parish Register, 15D 155/2, Norton Parish Register, DE 1555/1, Plan of Appleby Church Pews, 1832: 15D55/30. Probate Inventories: Thomas Parker PR1/36/50. Archdeaconry Court Proceedings, Appleby Penance, 1D41/4/LXXX/135, Presentment 1D41/4/XXXI/66

Derbyshire Record Office:

Gell Family Papers, D258, NRA 5438

Derbyshire Local History Library: Transcripts of genealogical references to the Gell Family in Wirksworth Parish Records, 1600-1900. Pedigrees transcribed by Thomas Norris INCE, 1799-1860

Particular thanks to Jess Jenkins, Assistant Archivist at the Leicestershire Record Office, for assistance with identifying Mary Parker, and for permission to reproduce extracts from the Appleby penance certificate. Thanks also to Richard Dunmore of Appleby for information about the church and the Parker homestead, and to Dr Simon Harratt for drawing my attention to the clerical politics of eighteenth-century Leicestershire.

© Alan Roberts, June 2009