Appleby History > Alan Roberts > Beginnings

Agricultural Beginnings:

Medieval Settlement and Marketing

by Alan Roberts

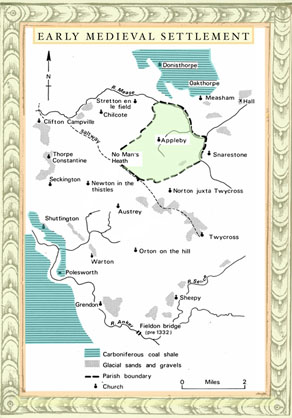

Map of Early Medieval Settlement With acknowledgements to Doris Unger Click image for larger view |

The District of the Midland Station

Straddling the central ridge dividing the catchment basins of the Mease and the Anker, Appleby lies at the very heart of an area described by the practical agriculturalist, William Marshall in 1787 as ‘The District of the Midland Station’. Although mixed farming combining livestock and grain was well established in this region by the late medieval period, the medieval farmers farmed mostly for subsistence, and to meet their feudal obligations such as averagium - the Appleby bondmen’s payment of newly-threshed corn and malt to the monks of Burton.

While there were some barren patches on the sandy uplands and the cold clays of the Ashby Wolds remained intractable, the soil was extremely productive. Recent glaciation has covered this part of the country with extensive surface deposits of sand, gravel and boulder clay which generations of farmers mixed with the underlying Keuper marl and sandstone to produce a rich loam, ‘equally apt to bear corn and grass’ as William Burton, Leicestershire’s celebrated antiquarian, observed in 1622. The farmers added manure to increase crop yields and lime to ‘mellow the soil in tillage and sweeten it in grass’. There were of course other sources of income like coal shale outcrops at Measham and Donisthorpe to the north, and at Shuttington, south-west of Austrey. But the surface pits operating at Measham from the early 1600s and at Shuttington by the 1690s made only a marginal contribution to the region's economy because there was no economical means of transporting the coal to the industrial centres where it was most needed until the construction of the Ashby canal in 1804.

Early Medieval Settlement

The map of medieval settlement (above) shows the towns and villages around Appleby in early medieval times. Richard Dunmore’s work on the origins of the parish has highlighted the historical importance of the Mease and Anker river valleys as a buffer zone between Mercia and the Danelaw. After the humiliating treaty of 877 which ceded a large part of East Mercia to the Danes, the area north of Watling Street was colonised by Danish settlers who moved up the Trent valley, establishing their administrative capital at Repton in Derbyshire. The Saxons had already established themselves on the best sites, which explains why the Old English place names tend to identify townships giving access to the more easily-worked, permeable soils while most of the Scandinavian place names describe settlements on secondary sites. Thus the Saxon -hams and -tuns (Measham, Snarestone, Norton, Shuttington, Warton) lie adjacent to sand and gravel outliers while the Danish thorpes and -bys (Donisthorpe, Oakthorpe, Ashby and Appleby) are sited on Sandstone or shale. The by element in Appleby indicates a Danish origin, although as Mr Dunmore suggests, it is possible that there was an earlier Saxon or even Romano-British settlement near here. The curious mention of a ‘spellow’ field in a fifteenth-century Appleby manorial land terrier points to the possible existence of a Saxon moot site within the parish.

Mixed farming was certainly well established in the region by 900 AD. The Domesday Book lists at least eighty separate place names (not all necessarily nucleated settlements) scattered along the two river valleys by 1066. The comparatively rare mention of woodland suggests that the inhabitants of the border region between the two rivers had cleared much of the oak and thorn forest that originally clothed the hill slopes and river flats. Domesday figures for population and plough teams suggests that there may have been about 3,500 people spread over some 120,000 acres in the thirty or so parishes in the immediate vicinity of Appleby.

Ancient Trade Routes

The ancient ridgeway which follows the county boundary between Appleby and Austrey is perhaps one of the oldest trade routes in the region. In eighteenth-century enclosure maps it is marked as ‘Salt Street’, which lends support to the suggestion that it originated as a prehistoric saltway giving access to the Cheshire salt pans. From Appleby it crosses No Man's Heath following the Mease as far as Harlaston, before its junction with the Tame at Salter’s Bridge. Another ancient ridgeway, the highway from Tamworth to Ashby de la Zouch, passes through the top half of Appleby parish to intersect Salt Street. This is probably part of the ‘Upper Saltway’ connecting the trading port of Saltfleet on the Lincolnshire coast to the Droitwich salt pans. The section of Salt Street branching off from Watling Street on the parish’s southwestern boundary was invested with a special, strategic importance in the early medieval period because after the partition of Mercia in 877 AD it was probably part of the southern limit of the Danelaw, allowing a natural buffer around Tamworth. It was incorporated into the shire boundary at a somewhat later date (perhaps as late as 1000 AD) - as a sort of political and cultural divide between ‘Danish’ Leicestershire and ‘Saxon’ Warwickshire.

Medieval Towns and Markets

The local market towns in early Norman times were not very large. Tamworth, the old Mercian capital, site of a ninth-century royal palace and mint, is only briefly mentioned in the Domesday survey apart from a reference to nearby manors contributing burgesses to the town. In fact Tamworth is the only town described as a ‘borough’ with burgesses or householders with burgage tenure. Mention of some of these burgesses living in nearby Drayton Basset working alongside villeins in the field suggests that the townsfolk mainly relied on agriculture. The nearest outside urban centre of any size was Nuneaton, south of Watling Street, with 88 recorded inhabitants. Ashby de la Zouch, Market Bosworth and Atherstone all record populations so small as to suggest that they were mere hamlets in 1086. Austrey, with 40 villagers and a priest, seems to have been one of the most densely-populated settlements in the entire region.

Frequent Domesday references to waste at Oakthorpe, Donisthorpe, Willesley and Measham, and the evidence of shrunken populations at places like Shackerstone and Norton, can probably be ascribed to the Conqueror’s savage campaign of 1068 which left a trail of destruction in its wake. Tamworth's borough status and the need for certain essential items like salt to be brought from further afield indicates that there was some trade being carried out in the region. But none of the surrounding towns could really be described as ‘urban’ centres. The Domesday evidence tends to suggest that most of the eleventh-century villagers did not produce enough surplus to supply the town markets.

But the emergence and expansion of local markets and an increase in the number of towns with borough status provides evidence of steady economic and commercial growth, one of the clear signs of economic recovery, after 1200. There was a difference between the ‘official’ market towns with permanent marketplace fixtures and burgage tenure, and local produce markets. By 1350 both Ashby and Atherstone had been granted burgage tenure. A measure of Ashby's relative importance was its grant of a Saturday market in 1260 - a privilege usually reserved for the larger market towns. Tamworth , whose charter was reconfirmed in 1336, was the only other town in the region to receive such a valuable grant. Although Atherstone and Tamworth were both hit with fire, pestilence and plague, both survived as market towns because their Saturday markets and special functions gave them an advantage over towns with weekday markets.

Medieval Communications and Trade

In medieval times a capillary network of customary ways between villages and manors serviced the great arteries of long distance trade. Trade helped to break down the natural isolation encouraged by communal farming. The emerging network of trade links between neighbouring towns exposes shifting patterns of social contact. In the 1350s for example Appleby bondsmen probably used the ridgeway to convey their customary averagium to Harlaston, receiving cartloads of unthreshed grain in exchange for their newly-threshed corn and malt. However this route had probably fallen into disuse by the late Tudor period. Frequent references to the maintenance of highways and bridges in quarter sessions presentments suggest increasing traffic along the network of highways, fords and packhorse bridges giving access to the rapidly expanding local market towns at Ashby, Tamworth and Atherstone.

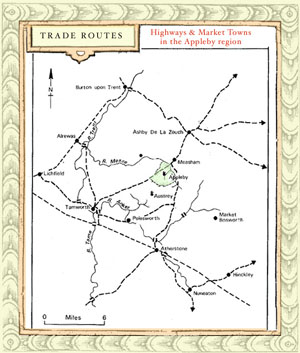

Medieval Markets & Roads With acknowledgements to Doris Unger Click image for larger view |

The map of medieval communication routes shows the relative position of markets and ‘highways’ in the later medieval period which saw a proliferation of charters for local markets. M.W.Beresford estimates that the Crown granted market rights to over 1,200 townships in England and Wales between 1227 and 1350. In addition to those already mentioned there were at least four other market charters within the region. Polesworth’s charter, which conferred rights to a weekly market on Thursdays and an annual fair from 20th-22nd July was one of the earliest. Similar grants for weekday markets were made to Bosworth (1285), Measham (1311), and Seal (1311).

The granting of markets and fairs on separate days from those of neighbouring towns was obviously meant to prevent excessive competition but it also provided villagers with a choice of markets, just as the staggering of annual fairs provided a circuit for itinerant traders. This sudden expansion of chartered towns and villages in a broad arc from the Eastern Lowlands to the Trent shows an increase in the demand for new trading outlets by 1350. Bracton's response, an enactment that no grants should be given to towns within a six and two-third mile radius of another, was a desperate attempt to prevent overcrowding. One of the reasons why many of the markets in the Mease and Anker valley region were only three or four miles apart was the lack of navigable waterways which made it difficult and expensive to transport bulk wheat and grain very far. At least one attempt to circumvent this problem, Lord Conway's scheme to make the tributaries of the Anker navigable as far as Austrey to bring corn to Fazeley mill, proved too costly and had to be abandoned after 1636.

Local evidence hints at the existence of another layer of marketing which has gone unrecorded in standard gazetteers and almanacks: the illegal, or ‘customary’ markets. Its hard to estimate how many customary markets there were but some hint of the extent of private trading is revealed in a list of Leicestershire markets and fairs drawn up in 1600 referring to Henry de Appleby's rights to hold a market in Overseal on the grounds that he had ‘free warren’ there. Henry also had rights to free warren in Little Appleby which suggests that he may have occasionally held markets there as well [Harleian MS 6700/3 ff.19, 49]. Austrey’s ‘butter cross’ at the upper end of the village, which local tradition ascribes to the monks of Burton may be another example of this sort of customary or private market.

The Ancient Parish and its Medieval Manors

The spiritual and secular lives of early modern English villagers were regulated by a complex system of local administration which comprised several, overlapping layers of authority. Ecclesiastical authority was exercised by the archdeacon and his officials who supervised the parochial clergy and the laity, while civil authority was exercised by the manorial and shire courts. David Hey has remarked upon ‘the extraordinary capacity for survival’ of ancient land divisions. Appleby’s boundaries, marked by the course of the River Mease extending in a broad arc on the northern and eastern flanks, the old shire boundary on the western edge and a long, unbroken hedgerow connecting up to the river on the south side probably date from Saxon times. The old shire boundary between Appleby and Austrey on the south-west was particularly important as it marked the border between Leicestershire and Warwickshire, the diocesan boundary between Lincoln and Lichfield and the limits of manorial jurisdiction. A series of ancient meres, hedgerows and field boundaries also divided Appleby from neighbouring Stretton in Derbyshire. As far as the villagers were concerned the parish boundary, familiarised by usage and ritual perambulations, was probably the most important administrative unit - besides defining the collection area for church tithes it marked the limits of their common fields. Farming was communally organised at parish level.

Before the administrative re-alignment of county boundaries in 1897 Appleby parish was divided between Leicestershire and Derbyshire. In 1622 William Burton observed that it was situated ‘upon the verie edge of the countie of Derby, with which it is so intermingled that the houses... cannot be distinguished which be of eyther shire’(!) Burton was probably exaggerating - the local Justices of the Peace would surely have known the territorial limits of their jurisdiction - thought some of the inhabitants may not have known which county they actually lived in. On the other hand there could have been no dispute about the physical bounds of the parish, most of the householders would have had a strong sense of parochial identification through their weekly attendance at church, the appointment of churchwardens, constables and overseers, and the regulation of the common fields. This parish-based system allowed the inhabitants to grow a great diversity of farm produce for market. An Appleby tithe dispute from 1629, for example, refers to levies of wheat, barley, oats and hay from the arable; pigs, geese, calves, colts, wool and lamb from yards and enclosures; and apples, pears and plums from the orchards.

Sources and Notes

William Marshall, The Rural Economy of the Midland Counties 2 Vols. London, 1790.

William Burton, Description of Leicestershire, R. Blome, Britannia: Or a Geographical Description of the Kingdom &c. London, 1673. John Speed, Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine London, 1611 (for descriptions of Leicestershire)

B.H. Cox, ‘Leicestershire Moot Sites, the Place Name Evidence’ , TLAS 47 (1971-2) p. 20 for moot site references. H.C. Darby and I.B. Terrett (eds.) Domesday Geography of Midland England (Camb. 1971)

F.T. Houghton gives an account of the ridgeway in ‘Salt Ways’, TBAS, xiv (1932), 1-17; Ridgeways continued to be used for the carriage of salt in the early 1700s. See D. Hey, Packmen; Carriers and Packhorse Roads (Leicester, 1980), 153. VCH Leics. III, 67, 78. The partition of Mercia is fleetingly mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. However, the exact origins of the shires remain hidden. C.V. Phythian-Adams suggests that Warwickshire may not have been defined earlier than 1007-16, although Leicestershire is not mentioned before 1066. ‘The Emergence of Rutland and the Making of the Realm’, Rutland Record, 1 (1980). Customary duties to provide grain are described in C. Kerry, ‘Bondage Tenure of Harlaston,Staffordshire,DAJ, xxii (1900), 84. CSPD (1635~6) p 450. M.W. Beresford, ‘The Origins of Medieval Boroughs in Warwickshire’ and ‘Additional Note: Atherstone’, Warwickshire History I, no. 2 (1969), no. 3 (1970)

B.E. Coates, ‘The Origin and Distribution of Markets and Fairs in Medieval Derbyshire’, DAJ 85

C.J.M. Moxon, A Social and Economic Survey of a Market Town, 1570-1720, Oxford D.Phil. 1971.

cf. David Hey's observation: ‘The parish framework in Shropshire might have been an arbitary one, but for many purposes it was the one that mattered’: Myddle, 20; Reference to customary perambulations of the boundaries in a 1628 Shuttington tithe dispute, VCH Warws. IV, 214. P. Sawyer (ed.) Medieval Settlement: Continuity and Change (London, 1977), 13; For reconstruction of parish boundaries from fragmentary evidence see,C.V. Phythian-Adams, ‘Continuity, Fields and Fission: the Making of a Midland Parish’. Department of English Local History Occasional Papers, 3 No. 4 (Leicester, 1978). W.R.O. CR 468. Nichols III, 1024; For produce see L.R.O. Appleby Tithe Dispute, 1D 41/VII/105-9.

© Alan Roberts