Appleby History > Alan Roberts > Population Growth & Marketing

Population Growth & Marketing in Early Modern Times

by Alan Roberts

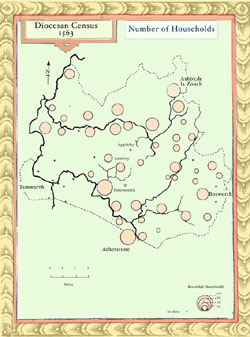

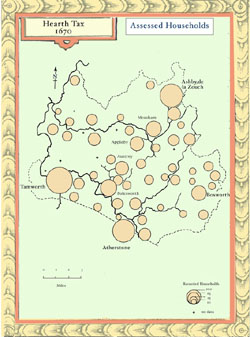

The period from mid sixteenth century onwards is known as the ‘early modern’ age because there are signs of a ‘modern’ economy and the breakdown of the old ‘feudal’ order. Between 1500-1700 there was a dramatic population increase in the survey region. Church census and subsidy returns for 28 of the 30 parishes show a 75 per cent increase in the numbers of listed households between 1563 and 1670, which is markedly above the Leicestershire average of 67 per cent over the same period. These increases were particularly noticeable in the market towns described in Richard Blome’s great seventeenth-century survey of the kingdom.

Richard Blome’s Flourishing and Declining Market Towns (Britannica, 1673)

|

|

1563 Census |

1670 HearthTax |

|

‘Flourishing’ |

|

|

|

Ashby de la Zouch |

77 |

248 |

Tamworth |

100 (est) |

323 |

Atherstone |

105 |

272 |

Declining or Decayed’ |

|

|

|

Seal |

62 |

160? |

|

Polesworth (incl. hamlets) |

105 |

255 |

|

Market Bosworth |

59 |

104 |

|

Measham |

72 |

112 |

|

Nuneaton |

188 |

278 |

|

The fastest growing towns, Ashby, Atherstone and Tamworth were at the intersection of trade routes. More isolated towns did not grow as fast. Comparison between the 1563 census and the 1670 hearth tax listings clearly show this drift of population to the better situated market towns astride the main trade routes, and a corresponding decline of the smaller trading centres. But the population figures do not tell the whole story. Some markets declined despite increased population. In 1563 Nuneaton, with 188 households, was the most populous town in the Anker valley. No town in the survey area even approached it in size. By 1670 however, this lead had been lost and Ashby, Tamworth and Atherstone, competed to challenge Nuneaton’s position as a connection point for the lucrative London trade.

The growth of these three local market towns in the Tudor period reorganised local transport links. In the medieval period access to markets was provided by packhorse bridges over the Anker and the Trent: Fieldon bridge gave easy access from Watling Street while the great bridge over the Trent at Burton served as a link to the north. Although the Burton bridge had fallen into a perilous state of disrepair by the early 1500s it continued to serve in the words of the abbott of Burton as ‘a comen passage to and fro many countrys to the grett releff and comforth of travellyng people’.

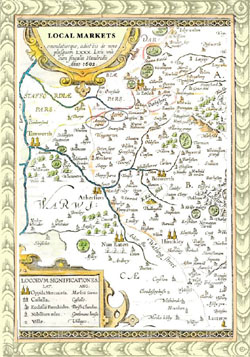

An early seventeenth-century map of based upon Christopher Saxton’s survey clearly shows the main market towns (‘Oppida Mercatoria’) in relation to their surrounding villages.

Ashby was particularly well placed to take advantage of the increased movement of goods and produce between towns. Standing astride the highway that linked Derby and Leicester, it was at the intersection of several major trade routes, one of the most important of which was the road which skirted around the edge of Charnwood Forest towards Nottingham at the head of the navigable Trent. This strategic position, reinforced by the town’s growing reputation as a centre for livestock and leather-tanning, largely accounts for its transformation from market village to major trading centre in little more than a century. Even allowing for gross underestimation of the number of households in the 1563 census, Ashby's population almost certainly more than doubled between 1563 and 1670. Much of this growth was the result of a local influx of workers into the craft industries. One estimate is that between 1658-61 a quarter of the householders recorded in the town register were engaged in leather trades and another 12 per cent were working in the cloth working industry.

Tamworth also experienced rapid expansion as a result of trade and migration. With more than 320 recorded households in 1670 it was the most populous town in the region by that date. Control of two vital bridges across the Anker and the Tame on the through route from London to Chester gave it a strategic trade advantage. Successive confirmations of borough privileges, including rights to a third additional fair in 1588, recognised Tamworth’s historic importance as ‘the seat of Saxon kings’. Although it was primarily a local market town, it did a brisk trade providing travellers with the staple bread, ale and accomodation, maintaining trading links as far afield as Bristol. The infusion of new life which followed Charles II’s reconfirmation of its borough's privileges in 1663 is well attested by Blome's account, ten years later, of its celebrated market, well served with corn, provisions and lean cattle.

Increased prosperity for the market towns meant a corresponding decline for the smaller local market villages in less favourable locations. Measham, ignominiously dismissed by Wyrley in 1596 as ‘a village belonging to Lord Shefield, in which are many coal mines, [but] little else worthy of remembrance’ was omitted altogether from Blome's gazetteer of market towns in 1673. Polesworth. described at the Dissolution as one of the ‘chiefest market towns’ in the kingdom is also omitted from Blome's list, its once thriving market being dismissed in 1720 as ‘long disused’. Seal was only one of many Leicestershire ‘market towns of good note and worth’ that had by 1622 according to Burton become ‘quite forlete [sic] and out of use’.

Even medium-sized towns, such as Atherstone and Market Bosworth, felt this drift of trade to the key marketing centres. In the medieval period Atherstone was an important staging post for movement down Watling Street to London; the southern access road into the region branched off Watling Street from here to cross the Anker and link up with the highway from Tamworth to Ashby. However, by 1675 the growing importance of Coventry as a nodal hub of the midland road system had significantly reduced the amount of traffic on Watling Street. Although Atherstone retained its importance as the collection point for the London carrier trade and a famous market for cheeses, its history from the early 1600s is one of slow decline.

Rough roads, packhorse bridges and ‘cledgy’ soils

Clearly, accessibility was a crucial factor governing the extent of a town’s marketing area. William Harrison's observation. that the common highways ‘in the clay or cledgy soil’ became ‘deep and troublesome in the winter half’ is confirmed by a succession of sixteenth and seventeenth-century travellers through the midlands. It is no accident that the most celebrated among them, Bishop Corbett John Evelyn, Thomas Baskerville, John Conyers and Celia Fiennes, all travelled on horseback rather than by coach. In 1790 William Marshall reported that the highway between Ashby and Tamworth was ‘almost impassable for several months of the year’ and he goes on to suggest that the road system had suffered ‘total neglect since the time of the Mercians’.

Of course rough roads did not necessarily disrupt trade. J.A. Chartres argues that travellers were always prone to exaggerate and that trade was seasonal so there was a natural slackening off in the winter months anyway. The adaptability of horses and horse-drawn carts to bad roads has been pointed out by writers like T.S. Willan, who cites Sir Robert Southwell’s report to the Royal Society in 1675 showing that 60 per cent of England’s land trade was carried by packhorse. Poor roads and high freight costs restricted the distances that villagers were prepared to travel to sell their heavier, more perishable farm produce. So while expensive, lightweight, luxury goods such as lace, and dyestuffs, travelled hundreds of miles and sheep were sometimes driven 40 to 50 miles to the great midlands sheep markets, corn rarely travelled more than 10 or 15 miles. The prohibitive cost of freight often exceeded the value of the corn where there was no cheap river transport.. This was the important factor that determined the orientation of villages to market towns and it probably explains why severe food shortages in Tamworth in 1598 were not relieved by massive imports from other parts of the country. Appleby farmers would have continued to sell their grain at the closest local markets, venturing further afield only to buy specialised products that were unavailable locally. And even this need was well catered for by early modern times. During the summer months a colourful army of petty chapmen, higglers and peddlars, families of travelling hawkers like the Dabbs of Atherstone and Nuneaton who are repeatedly mentioned in seventeenth-century toll books, went on a circuit of midland markets and fairs to meet a growing rural demand for trinkets and smallgoods.

Sources and Notes

Letter from the abbot of Burton re Burton Bridge in C.H. Underhill, A History of Burton on Trent(Burton, 1941), p. 168. William Wyrley cited in T. Bulmer’s History, Topography and Directory of Derbyshire (London, 1895 ed.)

J. Gould, ‘The Medieval Burgesses of Tamworth: their Liberties, Courts and Markets’ TSSAS 13 (1971-2)

John Ogilby published a series of strip maps of English roads in Britannia (London, 1975).

William Harrison, The Description of England, 1587, G. Edelen (Ithaca, 1968)

J.A. Chartres, ‘Road Carrying in England in the Seventeenth Century; Myth and Reality, EcHR 2nd Series, 30 (1977)

T.S. Willan, The Inland Trade (Manchester, 1976)

C. Platt, The English Medieval Town (London, 1976)

T. Kemp (ed) The Book of John Fisher, Town Clerk of Warwick [1580-1588] (Warwick, 1900).

Where did Appleby Inhabitants go to Market in Tudor and Stuart times?

Distance and the cost of conveyance were decisive factors which determined local trading patterns or marketing areas. Midland villagers often frequented two or three market towns, depending upon the produce and the possibilities of a good price. Appleby’s closest market towns were Ashby, Atherstone and Tamworth. Lichfield and Burton (12 miles to the northwest), Nuneaton and Market Bosworth (10 miles east and eight miles south-east respectively) formed an outer ring of market towns beyond the enclosing triangle. Poor roads and traffic congestion probably combined to discourage too frequent visits to these outlying markets. The market specialities may have played a part in encouraging attendance. Ashby and Tamworth were famous for their weekly livestock markets, Atherstone for its alehouses, cheeses and carrier services, Nuneaton and Market Bosworth for their annual horse fairs, while Lichfield and Burton had cornmarkets. (One Appleby farmer refers in his will to a bequest of barley and peas by ‘the measure now used at Burton on Trent’). While the Appleby villagers would have been familiar with the markets and fairs in all of these towns, they had no need to venture far to sell their produce. The fact that all except Bosworth held Saturday markets may have discouraged regular attendance at outlying markets because villagers who wished to go further afield would have had to either skirt around or go through one market to get to another.

While evidence of county segregation is sparse, proximity was probably the crucial factor in market attendance: farmers always prefer to take their grain and livestock by the shortest and most convenient route to market. Ashby and Tamworth both held Saturday livestock markets and there were regular markets and fairs at Measham and Polesworth so we might assume that on Saturdays many of the Appleby farmers drove their cattle to Ashby while their neighbours across the county line in Austrey took theirs to Tamworth. Dr J.D. Goodacre has found evidence to suggest that the county boundary near Lutterworth served in such a fashion to define the limits of that town’s ‘marketing area’. References to ‘foreigners’ in market town registers also provides some indication of the pattern of movement from outlying townships. Registrations of baptisms, marriages and burials in Tamworth between 1556-1635 for example suggest that the drift of people from outlying townships was largely confined to the area south of the Leicestershire county boundary. Market attendance was also influenced to some extent by customary ties based upon tenancy, landownership or kinship as for example in the case of the Wathew family, who were copyholders on the Appleby manor purchased by Wolstan Dixie of Market Bosworth in 1600 and who frequently attended Market Bosworth horse fairs in the early 1600s.

Sources and Notes

Professor Everitt points out that a farmer on foot could easily walk 8 or 10 miles and still return home before nightfall. For the principal produce markets in the midlands, Agrarian History of England and Wales IV, 492-5; Atherstone cottagers combined felt-making and tammy-weaving with the management of a smallholding and the carriage of goods from Nuneaton and Ashby: VCH Warws. III, 127.

Reference to bequest of barley and peas ‘by the measure now used at Burton-upon-Trent’: L.R.O. wills, Richard Wright of Appleby, 1588/64; An archdeaconry court case involving William Pecher of Appleby refers to Swepstone farmers’ cattle outside an alehouse in Atherstone market square; Maps showing the relative position and importance of local market towns in Dugdale's Warwickshire (1st ed., 1656), 636-7; R. Plot’s Natural History of Staffordshire (Oxford, 1686), frontis. In 1698 Celia Fiennes went from Tamworth to Lichfield in an hour on ‘a fine, new gravel road’. C. Morris, Celia Fiennes, 164. Had she attempted to travel from Appleby to Tamworth on Saturday she may have taken longer as the way would have been crowded with people taking produce to Tamworth from surrounding villages.

Goodacre. Lutterworth thesis, 33. Of 1,883 marriage, baptism and burial entries registered by extra-urban householders in Tamworth between 1558-1635, only 4 came from Leicestershire parishes (3 from Orton, 1 from Clifton Camville), 79% came from Warwickshire, 20% from Staffordshire and less than 1% from other counties. For reference to family attendances at horse fairs see: P. Edwards, ‘The Horse Trade in the Midlands in the Seventeenth Century’, AGHR 27 (1979), 93; I am grateful to Dr Edwards for allowing me to examine his records of the Bosworth horse fairs.

©Alan Roberts, October, 2000