Appleby History > In Focus > 23 - Making a Living

Chapter 23

Making a Living

Employment in Early Victorian Appleby

by Richard Dunmore

The 1841 census gives us for the first time a complete picture of the ways in which the villagers made a living. Earlier examples of the family breadwinners may be found in the parish registers, as we saw in a previous article, but these cannot provide a complete list because information is missing for those who were not involved in baptisms, marriages or burials at the time (1).

The census enumerator by contrast was asked to state 'Profession, Trade, Employment or of Independent Means' for each person in the parish. Clearly there were those, such as children and many wives and mothers, for whom this did not apply but, of the total parish population of 1075, an occupation entry was given for 416 of them - from professional men such as the rector and the surgeons (doctors) down to agricultural labourers and the lowliest 'poor widow'. The latter were not strictly occupations, but the Appleby enumerator listed them nevertheless. These were crossed out by the census superintendent, probably as he counted up the number of poor people in the parish.

Farmers and the Agricultural Community

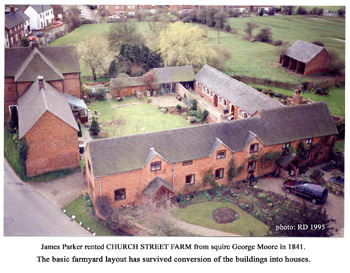

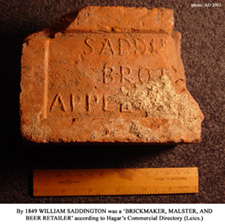

Appleby's inhabitants were largely dependent on agriculture, notably through the new farms into which the parish had been divided by the enclosures of 1772. Squire George Moore at the Hall, his uncle John Moore at the White House, the Rectory and Bosworth School Trustees were the principal land-owners and the majority of the farmers were their tenants. A few farmers, such as James Tunnadine and Bateman Saddington, owned smaller properties themselves.

Click for larger view |

In the 1841 census return, 28 farmers, one grazier and his brother, a cow dealer, were named. Allowing for the fact that this list included five farmer's sons working with their fathers, farm managers represented about 7% of those in gainful employment. The parish register information for 1813-21 gave a figure of 5% (2), but we cannot say with confidence that there was a real increase in the number of farm units, as there is no evidence of farms being split up.

The ages of farmers ranged between 20 and 70 years of age. Three were younger than 40 years, fourteen between 40 and 50 years and seven aged 55 to 70 years. Youth was no bar to renting a farm in a village where the squire himself was only 30 years of age.

Agricultural Labourers

Farming was very labour-intensive and it remained so until well into the 20th century. Working men found employment on the land, on a day to day basis, performing the many physically-hard manual jobs available. A total of 76 agricultural labourers were recorded in 1841, about 21% of the paid workers of the parish.

Working men of all ages from 20 to 70 years found employment as farm labourers. Apart from the young and the old, the spread through the age ranges was fairly even. Seven were under 30 years, nineteen were aged 30 to 35, nineteen were 40 to 45, fourteen were 50 to 55, thirteen were 60 to 65 and four were aged 70. (NB the 1841 census ages were usually rounded to the nearest 5 years).

The percentage of men who were agricultural labourers in 1813-21 was 42%, so the proportion relative to all those in gainful employment had apparently halved by 1841. The reason for this may be a switch from casual to contracted labour, many former agricultural labourers being taken on as farm servants, with more security of employment (see below).

Craftsmen and Tradesmen

There was always a demand for skilled workers in the agricultural world and this is reflected in the large number of craftsmen supporting the farming community. Many were concerned with horses, the main means of providing power and transport. The particular men performing jobs which required skills relating to the agricultural world were:

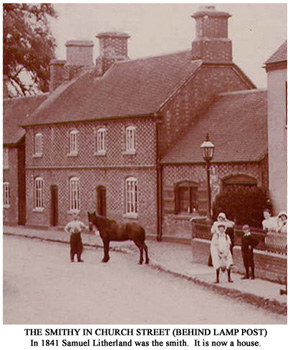

- 5 blacksmiths – shoeing horses and making wrought iron products for farm and home

- 2 farriers – shoeing smiths also acting as horse doctors

1 harness maker - 2 wheelwrights – making carts, wheels with their iron tyres (often fitted by the blacksmith)

- 2 gamekeepers – looking after the squire's game

- 1 gardener employed in the new hall grounds (3).

There were others whose skills were applicable in and beyond the farmyard:

- 3 sawyers

- 5 carpenters

- 6 joiners with 2 journeymen (assistant) joiners and an apprentice.

There was much new building work in the village in the 1830s (4). The carpenters and joiners would find work in the construction of houses and their fittings. Also involved in building construction were:

- 11 bricklayers with a bricklayers labourer

- 1 brick-maker – there were probably more of these in earlier decades

- 3 painters and

- 3 potters probably making earthenware products for house and farm.

Click images for larger views |

|

The making of beer was still a local occupation, although Bass & Co. owned the Black Horse:

- 6 coopers making casks and barrels

- 4 maltsters with 2 journeymen maltsters and an apprentice

- 3 publicans – at the Black Horse, the Crown and the Red Lion (Appleby Fields).

One of the farmers, Thomas Garner in Church Street, was also in the process of building a beer-house which within five years became the Adelaide Inn.

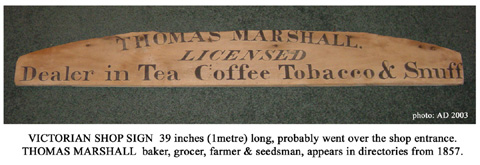

Food which could not be obtained from gardens and orchards came from local tradesmen:

- 1 baker

- 6 butchers

- 3 grocers with an assistant.

Other general requirements were available from:

- 1 shopkeeper

- 2 hawkers (one 'licensed') who presumably sold from door to door.

Cloth, clothing and footwear were made in the village by:

- 2 drapers

- 3 dressmakers

- 2 mantua (gown or dress) makers

- 2 stay-makers (makers of corsets)

- 1 stocking-maker (a cottage industry, requiring a stocking-frame)

- 1 straw-bonnet maker

- 9 tailors, with 2 apprentices, and

- 12 shoemakers with 1 apprentice (the larger numbers suggest cottage industries).

Domestic textile production was a declining small industry in the parish at this time (5). There were

- 2 cotton spinners

- 3 weavers (including 1 cotton weaver and 1 'custom weaver').

One man made a living as a rag gatherer.

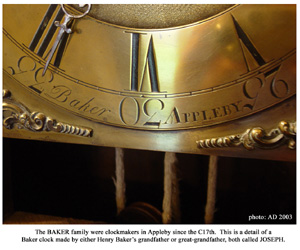

Henry Baker the clockmaker made and serviced clocks for the squire, the school and those in the village able to afford them.

Click images for larger views |

|

Two women were given more specific descriptions than the general term 'female servants' (see below), being called 'charwoman' and 'cook'.

Servants

Domestic service as a widespread occupation developed from the mid-18th century. This service industry was a by-product of the growth of successful towns which became social centres for the gentry (6). Servants also became an essential requirement in the running of country house estates developed in the wake of parliamentary enclosures. We have seen how the Moore family built luxurious mansions for themselves on their newly consolidated agricultural estate at Appleby (7). The upheaval in employment resulting from the enclosures meant that workmen had to adapt to new work patterns. Many new opportunities arose for women, especially young women, too.

Appleby parish registers record modest numbers of servants in the years before the national censuses: five servants recorded in 1698-1707 and five again in 1813-21 (1). Even though these counts are thought to be underestimates (because many servants were young and single and therefore less likely to appear in the register entries), the numbers of servants recorded in the 1841 census is quite astonishing: 71 female and 56 male servants were recorded.

Agricultural Servants

Some of the male servants in the census (a standard category abbreviated to M.S.) were almost certainly agricultural servants who, in the parish registers, were covered by the more general term agricultural labourer. Single servants 'lived in' and married ones were provided with a cottage and a small amount of land, as part of their remuneration. The agricultural servants would have had, or been trained in, a special skill, e.g. as shepherds or stock-men or working with horses. These were men who were required on the farm throughout the year.

The principal difference between servants and labourers was that, rather than being in casual day-to-day employment, servants were employed on a yearly contract. The security of such contracted employment was very attractive and the positions keenly sought. Annual hiring fairs during Wakes Week provided the occasions when workers offered their skills for hire but it is uncertain how long this practice continued at Appleby (8) (9).

Domestic Service

Female servants must generally have been employed as domestic servants 'living in'. These ranged from a young maid-of-all-work in a small household, doing general often quite arduous jobs, to a whole range of specialised servants in the large households, ranging from governess, housekeeper and cook to the various lower levels of maid.

At the bigger houses there would undoubtedly be male servants too: butler, footman, coachman and groom &c, but in smaller households one man might have a wide range of jobs to do. Although the census gives the names of all the servants, we are not told which job each of them performed. It is tempting to say that the older staff in the big houses held the senior positions but we cannot be sure.

Numbers of Households with Servants

There were 48 Appleby households with live-in servants, more than one fifth of the 222 inhabited dwellings recorded. The number in each house ranged from one or two in modest houses to 13 at the White House and 14 at Appleby Hall.

There were also five men-servants who did not 'live in', as they had their own homes. Being a male servant was their job. Of these five, two lived in the squire's cottages, two others were tenants of other people and the fifth owned his own cottage.

At Appleby Hall there were nine female and five male servants. The young squire had a young household. Apart from John Shutt, who was 37 years old, none of the others was more than 25. Not unexpectedly, the domestic staff at the White House, where the squire's uncle and aunts lived, were older. The men's ages ranged from 40 down to 14 years old, the women 65 down to 20 years old.

The larger farms and the public houses employed several servants, mainly young people, who lived in and performed much of the manual work and the less skilful tasks.

After the the two big houses, Barns Heath Farm was the next largest employer with seven servants. Thomas Foster and his wife lived there with a young baby, together with three female servants aged 14, 15 and 25, and four male servants aged 10, 15, 20 and 25. The Rectory employed five female servants, Upper Rectory Farm had three male and two female servants, and at the Red Lion Inn Samuel Cotton also employed three male and two female servants. At the Black Horse, by contrast, Samuel Parks had no servants living in, although it would be surprising if he employed no local people there. Lower Rectory Farm had one female and three male servants. The male servants on the farms must generally have been employed in agriculture.

There were three households who employed three servants, ten employed two and another thirty-three households had just one servant. Older couples, single or widowed people, indeed anyone 'of independent means' with a moderately large house needed to, and did, employ one, two or occasionally three servants. For example Joseph and Elizabeth Allcock lived at Hill House (No 1 Top Street) with two female servants and one male, the oldest being just 20 years old. Next door to the Church, 70 year old Sarah Tylecote had a 15 year old girl as servant.

Charles Mackie, the Headmaster employed two servants: a 'boy' and a 'maid' each 15 years old. Perhaps most poignantly, the squire's gamekeeper Henry Allwood aged 35 was a widower with 3 children between 4 and 10 years old. Without a female servant to run the home, his life would have been very difficult.

These are some examples (others will be found in my 1841 Census articles) which show above all that many young people in the village found employment in service in the village. The girls almost certainly had domestic duties in and about the house as perhaps did some of the younger boys. Young men were usually working in various capacities on the farms.

A Job for Youth

The bias towards youth is shown by the numbers in each of the age ranges. Although male servants at Appleby ranged up to 70 years old, most of them were relatively young. Three boys were between the ages of 11 and 12 years, sixteen youths were aged 13 to 17 and twenty-one were aged 18 to 20 (the largest group). The numbers then rapidly tail off: six were aged 25, two were 30, one was 35, three were 40, and one each were 50, 60 and 70 years old (the age of one other was not known). Being a male servant, whether domestic or agricultural, was a usually young man's job.

Agricultural labourers were employed in steady numbers at any age (see above). It seems likely that when it came to choosing agricultural servants, the employers preferred to choose younger men whom they could train for particular skills.

The numbers of female servants show an even greater bias towards youth, peaking at around 13 to 17 years old. An additional factor in their case was that marriage and childbirth curtailed their employment. There were four girls aged between 10 and 12 years, twenty-four aged 13 to 17, fourteen aged 20, twelve aged 25, seven aged 30, two each aged 35, 40 and 45 years, and one each aged 50, 55, 60 and 65 years.

In many places under-15s often gave a false age (10). However in Appleby the numbers of young boys (six) and girls (eight) recorded in service below this age suggests that a generally honest answer was given to the enumerator. In any case, the Appleby schoolmaster-enumerator would know the village boys, and many of the girls, well.

Professional People

There were ten people whom we would regard as professional i.e. their occupations required some scholastic education or training.

There were two ministers of religion in the parish, the Rector Revd John Echalaz and the Baptist minister Mr William Edwards at the Particular Baptist Chapel. The Headmaster of Appleby Grammar School was Revd Charles Mackie. Like Mr Echalaz, he was an ordained minister of the established church and occasionally assisted by officiating at baptisms and funerals (11).

Other schoolmasters in the village were Edwin Hague the English Master and John Anscombe the Writing Master, both at the Grammar School. Another schoolmaster, 50 year old William Wilson, was living with his wife and son in part of No 1 Black Horse Hill. His name does not occur in the Grammar School records. Maybe the family were visiting, or lodging temporarily, in the village.

A schoolmistress, 30 year old Mary Orvill with Martha, probably her younger sister, was apparently running a small private school in Church Street in the house that later became Tunnadine's ironmonger's shop. There were four children boarding with them, three girls and a boy. In 1841 the National School (built 1845 for girls) was yet to be built opposite the church.

The other professional people were two surgeons (doctors) and a veterinary surgeon. During the 19th century, 'vets' were gradually to take over the role of 'horse doctor' from the farriers (12).

People of Independent Means

In Appleby in 1841, there were twenty six people 'of independent means' with ages ranging from 25 to 80 years. The squire himself was recorded as 25 years old, although we know he was born in 1811 and so was really 30 (was the enumerator too polite or timid to enquire?). Two others were 30 or less, one aged 35, three 40, six 50, three 55, two 60, one 65, four 70 and one 80.

It is difficult to discern any particular pattern in these people of independent means except to observe that they were by no means all affluent. Although some were, others were clearly not so. Some employed servants, but a surprisingly large number (12 out of 26) did not, suggesting that their income was adequate but not large. Ten of those without servants were living alone, the other two were with a younger person probably a close relative. Seventeen of the 'independents' were women and nine were men and both groups were spread through the age range, from young men to elderly, perhaps widowed, women. There were however some younger women and some older men.

The Disadvantaged

Twenty four poor widows were listed in the census for Appleby in 1841. I suggested above that some of those of independent means had an income that was only adequate. Clearly there were others – the poor widows – who were not able to claim the dignity of 'independence'. The fact that these had not been removed to the workhouse suggests that they survived with help from their families and local charities (13).

There is one other entry which requires some comment: Benjamin Lunn of Birds Hill was described as 'idiot' (14). Nowadays we would shy away from such a pejorative term but the Victorians had no such sensitivities. He was living in one of the weavers cottages with younger brothers (one of whom was a weaver) and other members of the Lunn family were nearby.

Notes and References

1. In Focus 18: Table of Occupations in Appleby Parish 1698-1707 and 1813-1821

2. Using figures for those gainfully employed in 1813-21 (i.e. omitting the non-earning widows), about 6% of the sample were classed as farmers.

3. Aubrey Moore recalled that the Hall Head Gardener lived at the 'Octagonal' house (4 Atherstone Road): Tape Transcript of Conversationwith Arthur Crane, Richard Dunmore & Peter Moore, Bloxham, 1 October 1987.

4. In Focus 13, housing renewal and building

5. D Wright, A Survey of the Industrial and Commercial Activities of Joseph Wilkes in and around Measham in the late 18th Century, B.A. Hons. dissertation ,University of Nottingham, 1968: Calico weaving shops for 62 hand-looms were built in Appleby by Joseph Wilkes of Measham around 1790 and they remained in operation until at least 1819 when they were put up for sale. By this time the domestic industry was waning as factory production grew.

6. Alan Rogers, This was their World - approaches to Local History, BBC, 1972, p.85

7. In Focus 13, Appleby House/Hall, White House and Snarestone Lodge

8. Wakes Week in Appleby followed the feast of Michaelmas on 10th October (old style calendar, i.e. 11 days after 29th September; the calendar was corrected in 1752 by the removal of 11 days). Nichols, op. cit., p 432: 'The wake is kept on St Michael's day, old style'. Agricultural workmen had been hired at annual hiring fairs for many years. The tradition had its origins in the Statute of Labourers of 1351. The distinction between those hired annually (servants) and those hired daily (agricultural labourers) seems to have been drawn out by the standard questions of the census.

9. Evidence that hiring of Servants, both male and female, usually took place in Appleby from Michaelmas Day old style is in the Diary of Nathaniel Tunnadine which details his servants over the period 1821-1844*. Some examples show this:

1822 Sep 21 Hired Sarah Smith, Norton to serve 51 weeks .. came Oct 12th .. wage £4-4-0...

1823 Oct 1st Hired William Smith, Clifton, to serve 51 weeks .. wage £7-7-0 .. came Oct 13th ....

1824 Feb 29th Hired William Bowley to serve till Old Michaelmas, wage from Lady day to Old Michaelmas £5-0-0. Lady Day (March 25th and the start of the old style New Year) was 6 months earlier. Nathaniel Tunnadine's hirings appear to have been privately arranged, independent of a hiring fair, although using the same periods of hire. Perhaps by this time public hiring at Appleby had ceased and Wakes Week had become simply a holiday. Other entries show that hiring fairs at Ashby and Bagworth were still operating. Between 1825 and 1831 Mr Tunnadine paid for men to go to Ashby Statutes in search of employment elsewhere. Five or ten shillings cash was advanced for this and deducted from their annual wages. Also: 1830 Oct 13th Hired Thos. Jordan to serve 51 weeks, came again Oct 17 having been away 8 days, he was not paid anything for the odd week this Michaelmas because he did not serve it, being 3 days at Baggoth Statutes, and the remainder of the week, at going after places. Wage £8-0-0. Presumably his job-seeking was unsuccessful and Mr Tunnadine kept him on for the rest of the year for which he was paid £8.

*I am grateful to the late Mr Gordon Parker for generous access to the diary.

10. Alan Rogers, op.cit., p 93

11. Appleby Parish Registers, 1830s and 40s.

12. Jocelyn Bailey, The Village Blacksmith, Shire, 1977, p.17

13. For more about local charities see In Focus 18 The Growth of Wealth and Poverty in Appleby in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries

14. The word 'idiot' (in the Occupations column) is not easy to decipher. Like the 'poor widow' entries, it is crossed out so I do not think that I have confused the word for a real occupation.

©Richard Dunmore, January 2004

Previous article < Appleby's History In Focus > Next article

See also: The Clockmakers of Appleby