Appleby History > Memories > Growing up in the 1940's Part 3

Growing Up in the 1940s

Part 3: Village School Life

by Anne Silins

Appleby Magna, 1941 - 1945

Ashby-de-la-Zouch, 1945 - 1951

There were three school buildings in Appleby Magna when I started school in 1941. One was the Chapel Infants School, another was the Church School and the largest, the Appleby Magna Grammar School.

The Appleby Magna Grammar School was not in use as a school during the few years I attended school in Appleby, and that was a shame. This school building and the Moat House are both on the British Heritage List of National Trust sites. They are both important and historic buildings and they must be cared for. When I was a little girl the Grammar School building was mainly used for meetings and dances, and the grounds for the village summer fete. It was not until September 10th 1957 that the Sir John Moore Primary School came into existence.

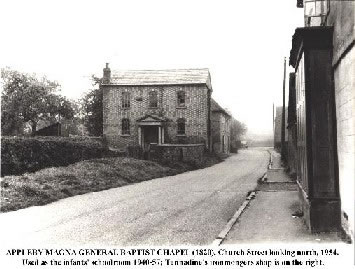

The Infants' Chapel School, Church Street

Picture of the Old General Baptist Chapel provided by Richard Dunmore from his book 'This Noble Foundation' |

My school days began in the one room Infants School just a short distance along Church Street from where I lived, so only a few yards from my home. It was called the Infant's Chapel School, not because they hoped we would all turn religious, but because the building had been the General Baptist Chapel. From 1940 until 1957 it was the Infant’s School. This building was one large room with a balcony across the back one third of the room. The teacher stood at what must have once been a pulpit. We sat in our seats and stared up at the teacher, who looked ‘god-like’ so high above us. Punishment, for even the smallest misbehaviour meant being sent up the stairs to the balcony area. This was not so bad, and I certainly did my time up those stairs. If you were quiet, and moved like a mouse, you could slowly work your way down to the front seats of the balcony and peer down at the teacher and the other pupils as they worked. Sometimes you were forgotten and I spent many hours watching children scratch their heads, pick away at their noses and generally do the things children of that age do instead of their classroom work.

I was by nature a loner, not lonely, but I wasn’t used to being with so many village children in one place. So starting school was a confusing and noisy experience for me. The other school children were an independent lot, adventurous in spirit and not always willing to do as the teacher asked. I soon got used to their harum-scarum ways, but always remained a bit of a prissy little girl. I tended to be an onlooker rather than a participant.

Temporary and sometimes unqualified teachers seemed to be the rule at Appleby's Infant Chapel School. Our teacher would try without much success to keep the young pupils in line, but it was difficult to keep us in class when the Hunt came through the village or when someone was needed to run errands at home, work in the garden or the allotment or look after younger siblings. Many children in my class were given ‘a good 'idin’ for not ‘stopping’ at home to help when needed. ‘A good 'idin' varied according to the temperament of the giver. It could be a good thrashing or a few clouts about the head. But these children tried to avoid that and if it couldn't be avoided, then they would brag about it. I was bewildered by their bragging talk, but watched and listened. I filed all this new information away in my head so that I could sit in the hay loft later and think it all through.

There were two play areas: a back yard with cinders covering the ground, and a front yard with grass and mud. The front yard we were told had been the cemetery so we had to be careful where we played. We shouldn’t walk on the graves, but we could never see where they were, so we walked all over the grass. Perhaps the story of the graves was made up by the older boys, just to scare we little girls. The cinder play-ground (yard) was a torment. If you slipped while skipping or running you received a nasty scrap and the teacher would have to dig out the tiny cinders from little girl’s injured knees. The boys had fewer scapes even though they all wore short pants, but never would they ask the teacher to clean their knees. A wipe with their hands, and only if the scape bled would they wipe it with the sleeve of their jacket or sweater. That same sleeve that they used to wipe their noses in winter.

The bigger boys happily related the tale of a small girl who had fallen into the Chapel School lavatory. They told us that the seat had given way, plunging the girl into the ooze below. They gave us the odorous and visual details of what she looked like when she was fished out. Little girls would hold ‘it’ until they got home rather than use that lavatory.. We small girls were very afraid the seat would once again give way and pitch one of us down that smelly black hole.

The Church School

After two years I advanced to the Church School. This school was opposite the Church, it had been opened in 1845. It was a fine old building but held far too many children. It contained two rooms, one big and one small. There were cloakrooms at each of the two front entrances and outhouses in the back playground. The play ground, ‘yard’, as we called it, was divided by a high brick wall. One side was for the boys and the other for the girls.

After two years I advanced to the Church School. This school was opposite the Church, it had been opened in 1845. It was a fine old building but held far too many children. It contained two rooms, one big and one small. There were cloakrooms at each of the two front entrances and outhouses in the back playground. The play ground, ‘yard’, as we called it, was divided by a high brick wall. One side was for the boys and the other for the girls.

Many levels of learning were attempted in this school. Sections of the large classroom held many different levels of schooling. The teacher and the pupils strained their ears to catch what was being said. The noise level tended to be pretty high as some students recited their times tables, while others recited poetry. The smaller room contained the students in the top or last year. Their numbers were small, as many had left to find work as soon as the pits or the farms would take them on. The head master's office was in this area and he taught these older children.

There was a big iron stove in each room. It was set up against the wall. An iron railing, or ‘guard’, as we called, it closed in the three open sides. This was to protected us from falling against the hot iron stove, it also served as a place to hang wet coats, hats and scarfs on rainy days. Our Wellington boots we cleaned off at the boot scraper just outside the door. We placed our boots around the guard rail, the open ends towards the heat, fanning out like the spokes of an enormous wheel. It came as a complete surprise to me that Wellington boots were not always waterproof footwear. Many children came to school with boots having holes and even great rips in the soles. Water from wading in the brook or in puddles went into these boots, and so when the boots came off in the school cloakroom water spilt out making the floor one enormous, slippery puddle. Of course, none of our clothing dried by the noon break, so we all slopped home for our dinner. The whole soggy lot of us repeated this slippery mess after the dinner break. Mitts were pulled onto hands that throughout the winter became raw and rough. We all suffered from chilblains. Children had no guarantee that coats or jackets would even dry overnight at home, even though at home clothes lines were strung up across the kitchen where, with luck their things might be almost dry the following morning.

The only way some of us escaped the usually ‘slightly-damp-from-the-last-outing’ clothing was to be quarantined at home for a childhood disease. Mumps, measles, chicken pox, scarlet fever or just the common cold could keep children indoors for two or three weeks each winter.

I really loathed winter clothes. I had to wear white cotton bloomers and then regulation navy bloomer, at the same time. Grandma said I couldn't wear anything but white next to my skin. Both pairs of bloomers were held up by stout elastic threaded through the waistband. Next came a white cotton vest, a petticoat, white cotton blouse, and finally the navy-blue pleated jumper or tunic. To-day, my grandchildren fling on their lightweight, weather-resistant, brightly coloured winter wear over casual, easy-care indoor clothes. They zip or Velcro up, pull on cosy, practical boots, insulated gloves and fashionable hats, and dash out of the door. If they do come home wet, they are spared the clinging odour of wet wool -- everything goes into the clothes dryer, and is quickly ready for the next trip outdoors.

"Children don't know how good they've got it to-day," we say. Back in the ‘dark ages’ women repaired the worn-through heels of school socks with many a well-placed tiny stitch. Those socks were never quite comfortable, however, you could always feel the seam of that darned ‘darned’ spot. Even our bloomers - ‘knickers’, were darned. I would watch girls wiggle in their seats as they adjusted around the thick seams of a darned hole. It was war time and the clothing coupons had to stretch just as far as the money did. Yes it is better today!

The day began, as it had at the Infants Church School, with Scripture lessons, singing of hymns and the recitation of the Lord's Prayer. Lessons followed until dinner time - reading, writing, arithmetic, history and geography. We all knew that the red bits on the giant map of the world belonged to the Empire. How proud we all were of those pink bits. In the afternoons the girls did needlework and sewing. Boys were out to a shed where they learned woodwork or they dug in the school garden. The front playground had been made into a "Dig for Victory" garden at the beginning of the war. Broad beans, runner beans, wax beans, potatoes and a variety of root vegetables grew there. This garden was a source of pride for the boys.

Our work was taken from the blackboards and we wrote on our slates. These slates had a wooden frame around the sides, many slates had cracks and many of the wooden frames gave us slivers in our hands. But in general they worked well. We wrote with a thin piece of slate called a slate pencil and the squeaking noise filled the room and sent shivers down our spines. To clean the slates, you spat on a piece of old rag brought from home and used lots of elbow grease. The best spitters usually had the cleanest slates.

Rules were strict, when not working with our hands we were expected to sit upright, with our hands folded in our lap. The teacher paraded the room with a wooden cane at the ready. "If I see one hand fidgeting, it’s the cane" she would warn. One day my skirt had bunched up under my bottom and as I had been told by Grandma to keep my knees covered, I reached down to set it straight; my unlucky day. Whack! There was a long red mark across the back of my hand. By the time I arrived home a good size blister had formed. I had learned my lesson from now on a little knee or leg showing was the least of my worries. I would just be unladylike, I had felt the sting of the cane. I did receive the cane on a few other occasions; talking was my downfall. I had become what the teacher called, a chatterbox. Yes, I received a few whacks of the cane on the palm of my hand for talking at the wrong time.

The former Church School, now the Church Hall |

Our teachers set great store in the Christmas pageant. Christmas enriched the school year and gave us great excitement. Each teacher hoped they could bring hope and a magical quality to the age old Christmas story. I was thrilled to be picked to be one of the shepherds. I was to have a Turkish towel draped over my head; have whiskers of cotton wool; wear Grandpa’s slippers; and use Grandma’s walking stick for my shepherd’s crook. The angels in our pageant had cheesecloth wings and haloes of tinsel and wire. The three wise men were draped in several colourful tablecloths. Mary and Joseph sat on a bale of hay with a china doll between them. My only line was to say "Behold in the Heavens, the Star of Bethlehem", which at the big event I shouted out when I got the signal from the teacher. I lost my whiskers of cotton wool, my crook got tangled with the Christmas tree which stood to one side of the stage, and I stumbled in the slippers. For my big finish I did a nose dive into the front row, where my grandparents were sitting. Mine was a dismal performance! The other children seemed to do quite well, and loud applause ended the evening. Some public figures get their first taste of public appearances when very young performing as Shepherds or Wisemen. Perhaps there is a lesson for future politicians; pick up your feet, and keep an eye on your crook.

Absent children were a problem at the school. Many pupils came from outlying areas a few miles away and were not used to being 'penned' up in a classroom, but were used to wandering freely in the countryside. They were a quiet group and kept mostly to themselves. Book learning seemed a waste of time to them and they had a difficult time keeping up with children in their age group. Many left school as soon as they could. The girls would go into service, the boys to work on local farms or to the pits and coal mines of Moira, Donisthorpe or Swadlicote. In the open country side these same young people could catch a bird or snare a rabbit with no fuss at all. Their survival skills came from every day life experiences. At planting and harvest time they would be absent because their families needed their wages to help the family purse, and some families just needed the help at home with younger children or in the family vegetable garden. I liked these silent, serious children from the edge of the village, they were kind and good with the little ones. Nearly all of them came from very large families. Lots of them were closely related, sometimes even an uncle and niece in the same class. You could get lost just trying to figure out who belonged with whom, and which family lived where.

In the village I had learned a lot of the local slang and used and understood it all. Words that in Canada years later no one would understood. Someone who complained for no reason would be called ‘mardy’. Someone who acted odd was ‘barmy’, ‘daft’ ‘gormless’ or a ‘goon’. Something or nothing became ‘owt’ and nowt’. Adults would tell children to stop ‘larking’ about’- acting foolishly. ‘Dropped off’‘ - didn’t mean fallen down, but rather ‘your Father has ‘dropped off ’ - he had just gone to sleep. ‘Slow coach’. I was often told I was a ‘slow coach’ - meaning I was as slow as the days of coach travel. Children were told to shut their ‘gob’ - mouth; or they would get cuffed about their ‘lugs’ - ears.

Ashby de la Zouch

After a couple of years at the Church School I was moved to the Girls School in North Street at Ashby-de-la-Zouch. I caught the bus in front of the Alms Houses and I had for company young women who worked in offices and factories in Ashby, also the girls and boys who attended Ashby Girls and Ashby Boys Grammar Schools. The bus made the journey through Snarestone and Measham. I got off at the stop in Market Street, then walked through the ‘alley’ to the Girls School.

At first I disliked the school and dreaded going. I did not like being new and not knowing anyone. Any excuse was cause to stay at home and I became very inventive with a sudden headache or stomach pains. This would pass as soon as the bus left. Then I was up at once and full of energy. My loneliness and dislike of the new school soon passed, and I got used to Ashby School, and best of all I made new friends..

When I started the Girls School I was issued a small, square cardboard box. I was completely at a loss as to what I should do with this beige coloured box. Then I was told to take the box and go to the school secretary’s office. The school secretary told me it was a gas mask, and each student in the school had one. "Hold the straps with your thumbs, and hook your chin into the bottom part, next pull the straps over your head." Instruction began. "Never hold the cylinder" (the tin bit), "to pull the mask off your face". This I was told would stretch the rubber and spoil the fit. At recess, we would practice putting on our masks. We would shout at each other, running round and round with outstretched arms, blowing hard to see who could make the rudest sound as the air was forced out past our cheeks. The celluloid eyepiece steamed up quickly and then we bumped into one another. I proudly took mine back and forth each day. The cardboard boxes wore out, and then we were given cylindrical metal cans. There was a string attached so that you could hang it from your neck or your shoulder. If I hung it from my neck, any boy could make a grab for it and I would receive a nasty jolt. So I would hang it from my shoulder. One day a boy on the bus grabbed it and tossed it like a football, out of the bus window. It survived this fall and because my name was painted on it, some man in the village found my scattered apparatus and returned it to me. I was very relieved. All Grandpa had to say was, "You’d just better hope Hitler doesn’t launch a gas attack today"

So there I was, at school in Ashby; a nervous, fidgety, couldn't sit still little girl. I bit my nails and always had a frown on my face. I must have been more nervous than usual on one particular day. Whatever the reason the teacher locked me in her cloakroom as punishment. The door closed and locked from the outside. With my hand on the knob, I turned to confront the darkness. Dry-mouthed, terrified and longing to protest my innocence, I inched along the wall, hitting my head on empty coat pegs. Only the yellow ribbon of light outlining the door was clear. I was positive there were monsters, all sorts of creatures in the dark. I was in that cloakroom the entire afternoon. I think that teacher just forgot me. At the end of the afternoon, the teacher let me out. I was curled up in a corner almost incoherent. She must have been alarmed. She took me to the main clock room and got down my coat and bag and then walked me to the school gates. I fled down the alley way to Market Street and the bus stop, not knowing if I was early or late. My black knickers were damp and my uniform stained, my weak bladder had let me down again. When I arrived home, Grandma did not ask questions she just took the knickers and threw them on the back of the fire. She sat close while we shared tea. My pride was hurt. Grandma's sister-in-law, Annie sometimes did substitute teaching at my new school and a message was passed that my punishment had been very unfair. After a while that teacher became a little kinder towards me, and now I enjoyed my new school.

My main meal of the day was now taken in the School dining room. When the bell rang at noon we all trooped into the echoing, big room and took our places at the tables, each table set for twelve students. Each table also had a senior prefect at the end closest to the kitchen. We all looked down at our plates as we said the usual ’for what we are about to receive....’. The plates were filled with over cooked potatoes, boiled meat and most often Brussel sprouts. These Brussel sprouts must have been boiled for at least seventeen hours. I hated boiled meat and boiled fish and I hated Brussel sprouts. I was never a good eater so I picked away until it was time for the pudding. "No pudding if you don’t finish the first course", the servers would yell. I hardly ever got to have pudding. I really didn’t mind. My least favourite pudding was tapioca. Tapioca we called ‘fish eyes and glue’, and that is exactly what it looked like. One day I told Uncle about the food. He had a suggestion. Under the kind of trestle table used for dinner at school, I would find a small shelf right below the main bracing. He suggested, why didn’t I put the bits I couldn’t eat, on this small shelf. He assured me that no one would know who had done it, and I would get my pudding. I would have to remember to change my seat frequently so that the bits of food didn’t always fall from the same spot when the tables were put away after dinner. This tactic worked for a few weeks, but the prefects and servers had seen this ploy before. I was caught out! Wouldn’t you know the day I was caught was the day of boiled meat and Brussels sprouts. I was told to sit until I had finished the whole plate, then if I was lucky I could have my pudding. I sat and stared at that plate for what seemed like hours, definitely most of the afternoon. I sat swinging my feet, and watched as the whole dining room and kitchen were cleaned.

Finally, towards three o’clock the staff got fed-up with me as they wanted to go home. They all stood around me with angry faces and I stuffed the food in my mouth. It was cold and covered in congealed fat. I retched and groaned the whole time. Now they announced I might have my pudding! Cold steamed pudding, covered in cold custard. It was awful! It hit my stomach like a piece of stone and I started to cry. This worked, I should have started to cry much sooner. I suspect the women all wanted to go home. "Go home." they said. By now it was time to run for the bus, and run I did.

When I returned to school in September 1948, we assembled at he Ashby Girls School, but were told to stand in line, two by two, and we were marched to the Ivanhoe Secondary Modern School in Burton Road. This was a mixed school, boys! That first day we girls were full of giggles, but after a few weeks boys in the classroom seemed natural and we soon stood on the sidelines happily cheering on the school football teams. I enjoyed the Ivanhoe School, it was there that I took the dreaded ‘Thirteen Plus’ examinations. I never did receive the results of this school examination because in May 1951 my father took me to Victoria, British Columbia, Canada with my Mother, sister and brother.

Canada - one of those ‘pink bits’ that I studied on the map at the Church School in Appleby Magna. Also at the Appleby Church School were very large photographs of Canadian prairie wheat fields, fishing villages and mountains covered in forest. Those photographs I remembered as our train crossed the entire width of Canada from Halifax to Vancouver. I have written about my memories of the schools of Appleby and Ashby, but the most important thing of all was the sound foundation those schools gave me. This foundation helped me in the many years of further education that I did in Canada. That was the gift it gave to me.

By Anne Silins, Canada 2001