Appleby History > Memories > Growing up in the 1940's Part 2

Growing Up in the 1940s

Part 2: A Young Girl's Life at Lower Rectory Farm

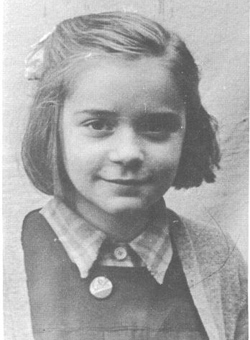

by Anne Silins

Ann Silins continues her tales of growing up in Appleby

In the last years of the War we left the Shop and moved to the family farm in Snarestone Lane - Lower Rectory Farm. I have very little memory of the move to the farm, probably because the moving took place during the day while I was away at school. I would have liked to be allowed to stay and share in the excitement, but that was not to be, I was to go to school as usual. I’m sure they didn’t want me under foot. On the final day of moving I was told that I should stay on the bus until it reached the Farm. Grandma would be waiting for me at the end of the driveway.

In the last years of the War we left the Shop and moved to the family farm in Snarestone Lane - Lower Rectory Farm. I have very little memory of the move to the farm, probably because the moving took place during the day while I was away at school. I would have liked to be allowed to stay and share in the excitement, but that was not to be, I was to go to school as usual. I’m sure they didn’t want me under foot. On the final day of moving I was told that I should stay on the bus until it reached the Farm. Grandma would be waiting for me at the end of the driveway.

The Farm house was a typical mid-Georgian house in the rectangular Midland style. It was of solid brick with a centre hall plan, two stories of living space and a large attic above and a dark cellar below. Built a little later and adjoining it on the south side, was the brew house and the wash house and above this were bedrooms. Some of Appleby and Snarestone parish had been “enclosed” by the Parliamentary act in 1760, and some farm houses in Leicestershire had names commemorating important events of that period. There was Quebec Farm, (Wolfe’s victory at Quebec), Botany Bay Farm, (the settling of Australia) and other episodes in England’s history.

Lower Rectory Farm situated in the south east corner of the village, in Snarestone Lane, was closer to Snarestone than to Appleby Magna. The original farm once belonged to the Church, hence the name Lower Rectory Farm. There was an Upper Rectory Farm too, which bordered us to the west, and that house, built on a rise, was of the same basic plan. .

Attached to the house were barns, stables, cowsheds, milk house, pig sties, kennels, the garage, tack sheds and even nine small brick pens where my Uncle kept his ferrets. On the second level were storage rooms, hay lofts and many rooms where the grain was stored in Autumn. All these buildings were arranged in a giant square. In the middle was a Dutch Barn with open sides. This Dutch barn was where Grandpa kept cows and pigs waiting for market. The whole area was cobbled with bricks and stones. Wide gutters drained the water and muck away from the buildings . At one end was the sheep dip trough, all in gray tiled splendour. A short distance from the north side of this square, was another Dutch Barn. This was the rick yard. Under this barn the corn and hay were kept dry until needed. On the south-west side and away from the house, was the tractor shed. Two tractors and the ploughs, harrows, rakes and seeders were kept there.

On that first evening the house looked strange and depressingly dim. But after I had my tea, I found I liked the small bedroom, directly over the brew house that I had claimed as my own. This room had a view to the south-west and was sunny and bright. From the hallway outside my bedroom door, another window looked towards the east and Snarestone, so I not only had the early morning sun from this south-east window, but I also had the last of the sun in the evening. I could lie in bed and hear the whistle of the train as it steamed its way along the grade to Snarestone. Also in the distance I could listen for the big lorries changing gears as they made their way up Birds Hill over by Measham.

At first I missed being in the heart of the village, but then I was astonished by a gift from my father, a new bicycle. Now I was free to travel back and forth to the village, that is, as frequently as my Grandparents would allow me to go

I came to love my life at Lower Rectory Farm.

An Aerial View of Lower Rectory Farm, 1953

I had believed that farm life was mud, darkness, inconvenience and loneliness. But I loved it once I was settled in and become very much a farm girl. Most of the farm house and outbuildings had been built in the years 1760 to 1780. The kitchen joined the stable wall and had a low ceiling with old, dark oak beams and an arched doorway. I believe this was much older than the main part of the house. There was a ‘built in’ kitchen range that had been fitted into the already existing space of an old, wide ‘open fire’ area. This had a big, wide chimney, that had been modified to fit the range. On one side of the range, extra space has been filled in with cupboards. On the other side was a ‘built in’ boiler. From this we had endless gallons of hot water for both the house and the milk room nearby. This little nook was also home for orphaned lambs in early spring. This boiler and iron cooking range were the only items of convenience.

Other fireplaces in the house were of morbid interest to me. When I stood in the fireplace I could look straight up and see the open sky above me. On the walls of the chimney some bricks jutted out forming a ladder, these would have been used as steps for the young, small chimney sweeps as they climbed and swept their way up and out of those chimneys. What sooty, dirty, painful work those young boys performed. I shivered as I looked and thought about them.

Surrounding the front garden was a stone wall built from huge slabs of stone, topped with even larger cut stones. These made an elevated walkway. No adults ever walked there, but I would prance along this raised pathway surveying all around me. In 1927 Appleby Hall had been pulled down and this wall was brought from there and re-built around the front garden at the Farm.

The landscape of neatly patterned fields, which we accept as "natural" today are really man made. Enclosure was achieved by taking the large open fields and dividing them with hedges or stone walls. In our district of Leicestershire it was all hedges. The medieval pattern of strips and furrows in the open fields were by no means completely obliterated with enclosure of the fields. This pattern of ridge and furrow was clearly shown in three of our pastures. I was to find that it was great fun to run up the ridges and down into the furrows.

During the War

Out in the countryside we seemed to be much more aware of the planes at night than we had been in the village. Grandpa and I would stand in the garden in the evening just before my bedtime, a roof of stars over our heads, Grandpa’s hands deep in his pockets and leaning back on his heels, he would say "It will be a big one tonight!". Enemy planes droned overhead on their way to the factories at Birmingham, Coventry and the breweries in Burton. I would stand close beside him and listen to the thumping of bombs as they dropped on their targets just over the horizon. The earth beneath our feet seemed to shiver as if it was injured and in pain. We would turn back towards the farm house, instinctively checking the windows to see if any sliver of light was showing. The blackout curtains had to be closed every night before it became dark, no light must show, or the Home Guard would be knocking on the door.

Some mornings, in the village, we would find the fields littered with silver foil strips. These had been dropped by planes to fool the radar. Sometimes the German planes dropped leaflets and we would rush out to collect handfuls; I don’t remember them being read, they were put onto the back of the fire.

Convoys came through the village with lorries full of American soldiers. It was said that they all had pockets full of chewing gum. We children had been warned repeatedly not to go near to the Twycross-Burton road to watch the convoys but we made our way to watch them in spite of the warnings. We would hide ourselves in the hedges and watch lorry after lorry go by. Some of the braver children would yell, “got any gum, chum!”. None was ever thrown our way, but then we didn’t really know what “gum” was, anyway. My Grandma never heard about these escapades thank goodness, or I would have been forbidden to leave the farm.

With so many men away fighting the farmers were short of labour. The government sent out prisoners-of-war to help with the planting and harvesting. These men were never kept behind barbed wire for very long. Within a few weeks of coming to the district most of them were billeted out with farmers as wageless workers. We had two Italian P.O.Ws. They became very much a part of the family. These P.O.W.’s had come to Leicestershire from Italy via the fighting in North Africa. Their style of life and their love of children quickly won the hearts of the whole village. Sometime during their first year with us they built me a wagon, I was very proud of it and, I even tried to harness old Mick to pull it. On Sundays they would walk down to the Snarestone Canal and come back with bundles of bulrushes which they would weave into baskets. The baskets became traps to catch small birds and these they cooked along with their hand made pasta. We were all a little sad when at the end of the war these two good men left. They left with never a backward glance. Could we blame them? They had families waiting in Italy. Grandma was a kind and generous woman and had been so to the two Italians, so she was sorry to have received only one letter from them afterwards.

One day some German P.O.W.s were brought to our village. They were marched from the Snarestone railway station, and had to pass the farm on their way to Appleby. They never seemed to be relaxed. They worked under strict control, with their own man to supervise the work-gang. We children were disappointed because none of them wore steel helmets or looked as horrible as we had expected. These were totally different men though. As they went about their work in the village they didn’t even bother to look at the children. They were not happy and the first thing they were going to do was try to escape. When the Italian and German prisoners met there was a lot of trouble between them. They yelled what we took to be insults at each other and made rude hand gestures. We were warned by P. C. Pointon to keep well away from them and any child not doing so would be taken straight to his or her parents.

V. E. Day, Victory in Europe, was on May 8th, 1945. There was dancing in Church Street in Appleby. Flags flew from every window and every telephone pole had the Morse Code sign for V. E. painted on it. My father had joined the Royal Air Force and spent much of his war time happily in Canada on Vancouver Island. He was a radio operator, or ‘sparks’ as they were called.

After the War

The war was over and my favourite Uncle at Lower Rectory Farm was old enough to join the Royal Air Force, something he had wanted to do for years. He was happy and I was unhappy, and not just because I missed his company, but also because I was often left alone in the evenings when my Grandparents would go to attend meetings, or go visiting, in the Village. Fright, dismay and cowardice were all emotions I felt at being left alone on that farm on a winter evening. I would watch from my bedroom window as they drove down the driveway. I would watch the tail-lights of the car until they disappeared behind the Stone family house in Snarestone Lane.

Now I was really alone, I would lie awake, not daring to move, hardly daring to breathe. My eyes darted here and there around the room, looking.....searching for what? I never saw anything in my room, but what an overwhelming loneliness, the awful fear that they had gone and abandoned me to the darkness.

Of course they had left me safely tucked into my bed, but this did not mean that I stayed there. Just the opposite. I would steal silently out of my bed, grasp my candlestick in my hand, carefully shielding it from the many drafts and I would enter the upstairs hallway. It was a sign of how brave I could be to step over the threshold of every room, my breath shallow, my heart knocking against my ribs, always prepared to meet some horror. The horror was never there, but it might be. We all have our share of night time fears. Mine was the imagined, ‘Mr. Fearsome’.

As I moved out into the upstairs hallway drafts from the many doorways and the two staircases caused the flame of my candle to jump about and flare up. Shadows leaped along the walls, making me catch my breath. The door to the billiard room was held shut with a small piece of string. It was most likely ‘binder twine’ from the rick yard. Drafts and wind would catch this door making it bang and squeak. After several evenings of listening to this banging, squeaking door, I found a piece of bailing wire and wired it tightly shut. Every noise scared me and most especially when ‘old Mick’ the dog in the yard would howl. My hair seemed to stand on end and tingle on my head. I could hear the train as it made its way up the grade to Snarestone. It always whistled as it approached Parkes’ farm and then ‘old Mick’ would howl again. Looking from my bedroom window I could watch the headlights of the lorries as they climbed up Bird’s Hill and on clear, winter nights I could hear the drivers changing the gears.

After checking each room, I would set the candle-stick down on the bedside table and then I would crawl into the wardrobe in my room. I had my dressing gown tucked around me for warmth and my Girl Guide whistle firmly clenched in my hand. If ‘Mr. Fearsome’ came I had decided I would blow that whistle as loud as possible. The fact that no one could hear me made the whole idea foolish, but the whistle remained a comfort. In the wardrobe I listened for every stroke of the Church clock, and when it struck ten o’clock I knew my Grandparents would soon be home. I stayed hidden in that comforting wardrobe until I heard the car turn into the driveway.

There was one night when I was nearly caught in the wardrobe. I must have been very sleepy. I dozed off. The car changed gears as my Grandpa turned into the yard and I jumped. As I jumped something brushed across my face, something furry and light. I was out of that wardrobe and into my bed in a flash, my heart was pounding, my face was flushed and I was sweating. Grandma came into my room to check on me. She laid a hand on my forehead and found I was very hot and very sweaty. Alarmed she called to Grandpa. “Anne is sick”, she yelled, and she shook me to wake me up. Of course I was very awake. A cup of tea was offered. “Yes”, I murmured, in a voice I didn’t recognize. Both Grandparents left for the kitchen, Grandma to make tea, Grandpa to telephone Dr. Salmon.

As they thumped down the front stairs, I got out of my bed like a shot. I had to find out what was in that wardrobe. I was brave now they were home. There, hanging from a peg in the wardrobe, was my furry creature. It was Grandma’s fox fur stole. I jumped back into bed ready to enjoy my cup of tea from the kitchen. The Doctor came and being a wise man, he understood right away what was troubling me. He mentioned that perhaps, I should not be left alone so much in the evenings. Soon afterwards a young women from the village came to stay, and I slept as a young girl should sleep. I didn’t even mind when the young girl’s boy friend appeared at the back door, just as my Grandparents disappeared down the driveway. I kept her secret secure and I was thankful for their presence.

At Lower Rectory Farm, as at all the farms in the village, we had many “stop at the door” visitors, some were welcome and some not. The most frightening visitor was the gypsy. There was a favourite camping site down by the Snarestone Brook. On some mornings, from my school bus window, I would see that they had set up camp on the wide grass verge. Tall, brown skinned men, and women in long, brightly coloured dresses would be starting their morning fires beside their caravans. It was the women who would come to the farm house door to sell clothes pegs, dishcloths and fancy combs. Lace was a specialty of the group that frequented our area. Gypsy women would also offer to tell your fortune. ”If you cross my palm with a piece of silver”, they would say. They could tell your fortune by cards, tea leaves, palmistry, astrology or even a crystal ball. The older gypsy women also said they could charm away warts and cure horses of disease. It was whispered in the village that they were skilled in making herbal remedies and love potions too. Being a timid little girl I was always ready to hide from them just in case they decided to put ‘the evil eye’ on me. Grandpa didn’t seem to mind them stopping beside his meadow and often told them they could let their horses graze there for a few days.

Another visitor to the farm was the ‘rag and bone’ man. He would take any old pieces of cloth, old pans, bones and any scraps of metal. This ‘rag and bone’ man had to keep awake and guide his old mare to each farm, he had no regular route like the bread man or the coal man. The horses of the bread man and the coal man knew their way without being guided, they just turned into each farm driveway as they delivered on their regular route throughout the village. The bread man once told me that at the end of his route he could just let the horse find its own way home, and he would do it, this way the bread man caught ‘forty winks’. The coal man was Mr. Jones from Measham, his horse was also familiar with the route. Mr. Jones lifted the dirty sacks onto his back, carried them to the side of the house and then stooped over as he let the coal pour from the bag over his shoulder.

A visitor I did not like to see was the ‘knacker man’. He came to take away old horses. It was sad indeed, that horses, after years of faithful service, would be taken away to be made into glue and fertilizer. No farmer liked to see his noble old horse led away. Many farmers just kept an old horse in a pasture, giving it the retirement it deserved. Some farmers were know to shot the animal when it could no longer graze. A huge hole would need to be dug by a machine and then a tractor would pull the large animal into the hole and cover it over. Tramps always came to the back door. Most tramps were harmless and were very willing to do some job for a meal and perhaps permission to sleep overnight in a dry barn. A meal was usually given them, but I was warned by Grandma to keep well away from them during their stay. They seemed to arrive in cycles. There were seasons with plenty, when they were all over the place, then a period with none at all. Some were amateurs, all fumbles and sad. Others were professionals, having made an art of asking for handouts with dignity. There was also an art in the tactics needed to say NO, Grandma was good at this, but Grandpa was usually an easy mark.

Down in the village and at school in Ashby, the big word ‘sex’ kept coming into our young girl conversations. I began to keep my eyes and ears open around the farm, listening in on conversations that were not meant for my ears. In those days we were not given any sex education in school and in my case not at home either. Grandma was quite Victorian, and she never thought to tell me such things. In the village we listened to the older girls. Evidently there were good girls and bad girls, and it was the bad girls who got themselves ‘with child’, pregnant. They very seldom gave the baby up for adoption, but the baby was kept in the family and raised as another sibling.

I was determined to learn about this elusive ‘sex business’. I discovered, quite by accident one Saturday dinner time, that the bull was to be put in a special stall with a certain, special cow. My ears and my mind took all this information in and I decided to see how I could get into the loft above this special stall. Here I thought I could hide in the hay, lay down on my tummy and watch the activities below through a gap or a loose knot hole. I would have a front row seat to the positioning and bellowing of the bull as he and the cow got to know each other. The mechanics of the whole business remained a bit of a mystery to me, but I was going to learn as farm girls do, by observation.

I made my way through the orchard to the back of the barns. A convenient ladder was against the wall where it gave access to a loft door. Up I went and made my way to the loft above the stall which was of interest to me. I waited and watched, I dallied a while to make sure I didn’t miss anything, making sure I saw all there was to see. Then I started back towards the ladder. No ladder! While I had been watching the bovine activities a worker had taken my ladder away. I was stranded 15 feet above the ground. What to do? Yell for help? Not a good idea. It wouldn’t take long for Grandma to figure out what I had been doing. Jump to the ground? I would most likely break my leg, or worse, break both legs. I could wait it out until I was missed at tea time, but Grandma’s conclusion would be the same. I made my way back into the lofts.

Although there were many places to descend, none were equipped with a ladder. After searching for some time, I came across an old length of rope. I fastened it to a hook on the wall. The rope came to within a couple of feet of the ground and down I slid. I skinned my hands quite badly, but I was down on the ground. I announced at tea time that I fallen off the garden wall. This seemed to satisfy my Grandparents and they bandaged my sore hands. My observations from the loft I shared in the village the next day with my girl friends. Older girls shrieked with laughter, but we younger girls only giggled, because we were still confused and mystified, and we remained so for some years to come.

Leaving Appleby

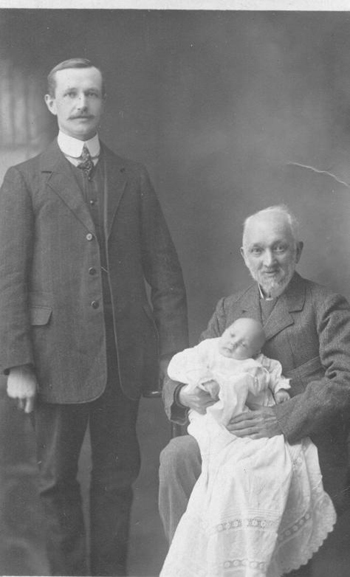

Left to Right - Charles Thomas Bates; (baby) Charles Rowland Bates; Charles Bates. 1912 |

Spring 1950 and my parents, my brother and sister came to live at Lower Rectory Farm. My parents were making big changes in their lives and these changes included me. My father had been in Canada for much of the war and he very much wanted to return to live in British Columbia. He, my Mother and we three children were all to go and start a new life there.

Looking back on my life with my Grandparents, I think they had done too good a job of shielding me from the harder parts of life. And by leaving me alone a great deal of the time, they had inadvertently made me some what self reliant. My evenings were quiet and I usually read until I fell asleep. Grandpa had a favourite poem he used to recite to me, ‘Leisure’ by the Welsh poet W.H. Davies. It lingered in my subconscious and I learned the lessons of it well. “What is this life, if, full of care, we have not time to stand and stare,” it begins. I took great enjoyment from walking alone in my spare time, across the fields and around the village. I kept my eyes open, little things around the farm and village took on importance and provided pleasure as I observed them in my wanderings. I couldn’t bear to think of leaving all this quietness and beauty which was Appleby. But leaving Appleby now was a reality. I was confused by this big change, a change to big to contemplate.

Preparations began. My Mother started to pack. She bought two huge brown suitcases at the Ashby Market. These were to hold our clothes. Next came boxes for household essentials. Pots, pan, dishes and linens filled the boxes. We even found a corner for my Mother’s Singer sewing machine. Each of us would be allowed one small suitcase on board ship. What I was told repeatedly was that this one small suitcase would have to hold all I would need for seven days at sea and five days on a train across the breathe of Canada. I had looked with fascination at the big world map at the front of my class room. I knew that huge pink piece was a country called Canada. But five days to cross a single country by train, this I didn’t believe.

My Father left three weeks ahead of us, travelling on the S. S. Europa. The newspaper had the following article about my Father leaving Appleby.

“Mr. Charles Rowland Bates, 35 yrs. old, ex-airman of Lower Rectory Farm arrived in Vancouver last week, a few miles from where he and his family - who sail from Plymouth on Saturday May 9 th - are to make their home. A native of Appleby Mr. Bates served in Canada as a radar operator in the Royal Air Force during the war, and he believes he will find more opportunities there for a career on the land. Looking forward to rejoining her husband is Mrs. Margaret Bates, eighth daughter, (of ten daughters) of Mr.Herbert Sutton, who farmed at Snarestone, and her three children Anne (13), Kathleen (9) and son Gordon (4). The emigrant is the eldest of the four boys in the Bates family. One brother is in the Air Force, one at home, one in business in London and a married sister at Glooston.” The Appleby Sunday School presented me with a hymn and prayer book on my last Sunday. The following was in the newspaper the next day.

“The two Sunday School teachers - Mrs. D. Gothard and Mrs. E. Dennis, and the children attending the St. Michael’s Sunday School have presented Anne Bates with a hymn and prayer book. Anne is leaving with her parents to make a new home in Canada. She has been a scholar for a very long time, and her fellow scholars wish to extend their best wishes to her on her departure.”

The sad, sad day came to leave my Grandparents, the farm, Appleby and England. All familiar things would be left behind. I had a final look around the village, the church, the farm, the garden. The last hugs from the family. My Grandma said her goodbye in the kitchen. My Grandpa was standing under the big oak tree by himself. He didn’t want to be among the rest of the kisses, tears and promises to write. He said nothing; he just looked at me, his eyes full of tears. He then turned and walked away up the field. I can still see him, shoulders hunched over, hands deep in his pockets, the dogs around his ankles happy for the unexpected walk.

On May 19th 1951 we boarded that same S. S. Europa that my Father had travelled on, bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

I think perhaps, country people get far more attached to things around them than city people. Everything is so real and one learns every stick and stone, every field, every tree, hedge - everything. Even with the excitement of the journey, I knew deep down that I was going to miss the familiar countryside of Appleby.

We travelled to Plymouth via London. My Mother reported to the Shipping Office. Our ship, the S.S.Europa, was anchored off Plymouth Hoe. We learned that we were to go out to this ship on a tender. The tender was a small boat which ferried us out and then transferred us to the ship at sea. One look from the window of the Shipping Office at that ship in the harbour and I knew this was going to be impossible. However, once the paperwork was completed I bravely jumped with both feet from the dock to the gangplank. I needed my departure to be significant. I was going to jump into this new life.

Rumours on board the tender said that passengers ahead of us had a difficult time transferring from one ship to the other. Ours would be easier my Mother told us because the tide was changing. My Mother knew nothing about tides and she had never been to sea before, but we believed her. The S.S. Europa looked enormous as the small tender got along side. A covered gangway was rigged between the ships and very quickly suitcases, trunks and assorted luggage was being moved overhead by pulleys. The time had come to walk the gangway. I felt like Peter Pan, the officer looked like Captain Hook, and that was no gangway, but a gangplank. My sister started across fearlessly, there was nothing for me to do but follow. My young brother had a few coins in his pocket, and as he walked the gangway he threw the coins into the sea. He had been told that Canadians had their own coinage.

Sunset that evening was brilliant, which seemed a good omen. We were all on deck when the engines started, all on deck to see the coastline of England fall behind us. My feelings were mixed, sadness and excitement. At age thirteen years, I was very excited about seeing new places. My Father had promised us such a beautiful country, Canada. There would be forests, lakes, prairies, mountains and the five day railway journey to the far side of Canada. But even with thoughts of all this ahead of me, I already missed the quiet footpaths and laneways of Appleby Magna. That home village where each house was familiar to me.

By Anne Silins (nee Bates)

Part 3 - Village School Life in the 1940's